Unlocking Cellular Complexity: Miller & Levine’s Essential Insights on Genetics and Protein Synthesis

Unlocking Cellular Complexity: Miller & Levine’s Essential Insights on Genetics and Protein Synthesis

A deep dive into the foundational principles of biology reveals that mastering cellular function—particularly the intricate dance of genetic information from DNA to protein—remains a cornerstone of scientific literacy. Miller and Levine’s Biology Assessment 18, specifically Exercises 1 and 20, delivers a focused exploration of two pivotal processes: translating genetic code into functional proteins and the regulatory mechanisms governing gene expression. These exercises, central to unit 1 and unit 20, challenge students to bridge molecular mechanisms with biological outcomes, sharpening comprehension of how life operates at the cellular level.

Through carefully crafted questions and conceptual challenges, the assessment reinforces core ideas that underpin advanced biological study and application. Exercise 1 in Miller & Levine’s Assessment 18 zeroes in on DNA as the blueprint of inheritance, tracing its central role in encoding life’s instructions. The DNA molecule, composed of two antiparallel strands forming a double helix, carries genetic information through sequences of nucleotide bases—adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C).

Each triplet of bases, known as a codon, specifies a particular amino acid or signals the start or stop of protein synthesis. As the assessment emphasizes, “Each codon is a molecular instruction thread, translating genetic blueprints into amino acid patterns that form functional proteins.” This coding language ensures fidelity in genetic transmission, yet the journey from gene to protein involves layered complexity, including RNA transcription and ribosomal decoding. What distinguishes this process is its precision: as students learn in Assessment 18’s first exercise, transcription begins when RNA polymerase binds to a gene’s promoter region, synthesizing a complementary messenger RNA (mRNA) strand.

The mRNA then matures through processing—capping, polyadenylation, and splicing—before exiting the nucleus. From there, translation unfolds at the ribosome, where transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules deliver amino acids in sequence dictated by the mRNA codons. As the Miller & Levine Assessment 1 reveals, a single gene may yield multiple proteins through alternative splicing, a mechanism expanding proteomic diversity without increasing gene number.

“This molecular flexibility illustrates nature’s efficiency,” the text notes, “enabling specialized functions from a limited genetic library.” Exercise 20 extends this understanding by probing the dynamic regulation of gene expression—how cells control when and how genes are activated. Unlike static genes, expression is responsive to environmental cues, developmental signals, and cellular needs. The assessment highlights key regulatory elements: promoters and enhancers act as switches, guiding RNA polymerase to initiate transcription, while repressors block this access.

Regulatory proteins bind specific DNA sequences near genes, modulating transcription rates in response to signals such as nutrient availability or stress. Post-transcriptional changes further refine protein output—alternative splicing, mRNA stability, and translational control allow a single gene to generate varied protein isoforms, fine-tuning cellular behavior. As the Miller & Levine test clarifies, “Regulation ensures proteins are built only when needed, conserving energy and enabling precise physiological responses.” The integration of these mechanisms underscores a central theme in modern biology: genes are not passive blueprints but active components in a responsive, dynamic system.

Assessment 18’s 20th exercise consolidates this insight, illustrating how transcription, RNA processing, and translation coordinate with regulatory networks to produce functional proteins under precisely controlled conditions. “Cells do not merely replicate DNA,” the assessment states clearly, “they interpret it—expressing genes only in the right place, at the right time, and in the right amount.” This nuanced control underpins development, differentiation, and adaptation, revealing the sophisticated machinery sustaining life.

Related Post

What Is Kurt Russell's Diagnosis? Unfolding the Story Behind His Health Journey

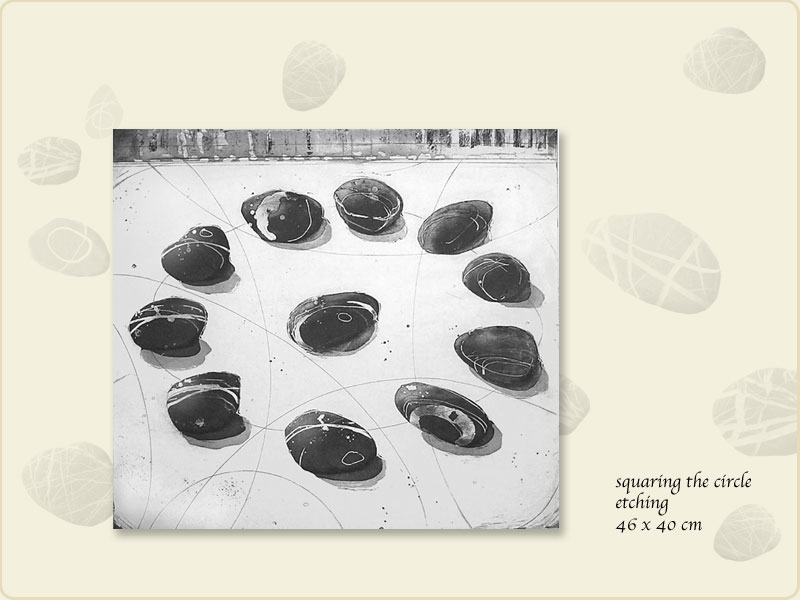

Apple Pay & Tesla App: Squaring the Circle on Seamless Payments

Understanding Atpl Brain Disease Causes Symptoms And Treatment

Hisashi Ouchi Death Picture: The Human Cost Behind Japan’s Most Infamous Nuclear Tragedy