What Is the Continent of China? Uncovering Its Geography, Identity, and Global Significance

What Is the Continent of China? Uncovering Its Geography, Identity, and Global Significance

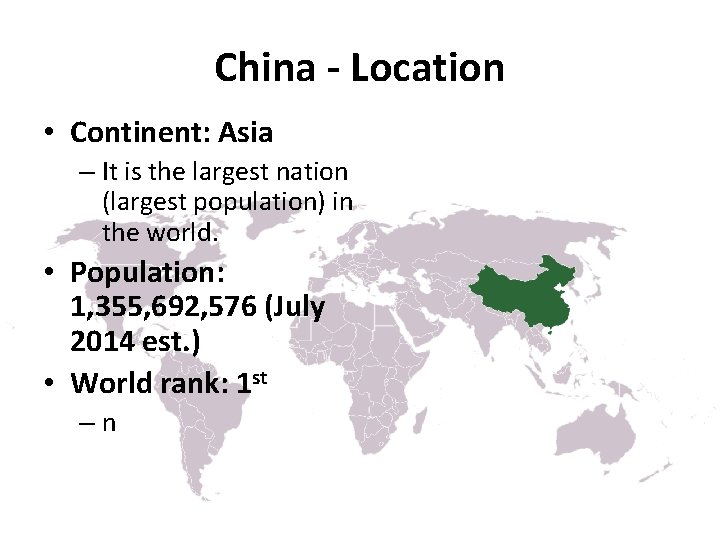

China, often perceived through the lens of a single nation-state, occupies a broader geographical and demographic reality as a continent-sized power bloc—the only country spanning an entire continental landmass. While globally recognized as both a country and a continent, the concept of “the continent of China” extends well beyond politics into geography, history, and cultural identity. This article unpacks the full scope of China’s continental presence, exploring how its vast territory shapes its global influence, environmental dynamics, and demographic complexity.

The Geographical Scope: Defining the Continent of China

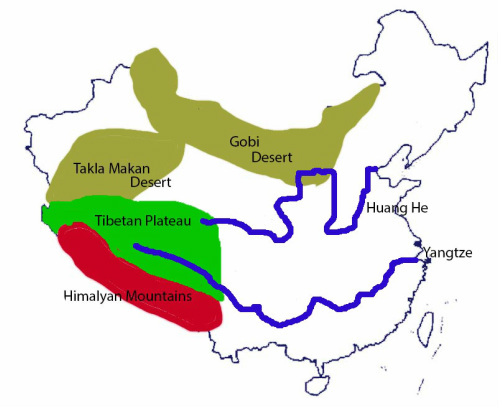

Contrary to common misconception, “China” refers not to a geographical continent in the strict scientific sense—where continents are defined by tectonic plates and distinct landmasses—but to a powerful nation-state commanding a sprawling continent-sized territory. The People’s Republic of China occupies approximately 9.6 million square kilometers (3.7 million square miles), making it the third-largest country by area, after Russia and Canada. This immense expanse stretches from the Gobi Desert in the north to the tropical shores of Hainan Island in the south, and from the Tibetan Plateau in the southwest to the coastal margins of the East Asian Sea.China borders fourteen countries—more than any other sovereign nation—including Russia, India, Kazakhstan, and Vietnam, underscoring its continental footprint. Its terrain is diverse and dynamic: - The northern reaches include the arid expanses of the Tibetan Plateau, the world’s highest continental region, averaging over 4,500 meters (14,800 feet) in elevation. - The interior features vast plateaus, deep river valleys like the Yellow River basin, and thick forest systems in provinces such as Yunnan.

- The east hosts the densely populated North China Plain, a breadbasket supporting hundreds of millions. - The southwest is marked by the rugged Yunnan-Guizhou highlands and karst landscapes, while the southeast includes fertile lowlands and coastal deltas. - To the north, the Gobi and Taklamakan Deserts form natural barriers shaping historical trade and defense patterns.

This staggering variety of topography positions China’s territory as a continental mosaic rather than a flat expanse, influencing climate patterns, biodiversity, and human settlement across regions.

Despite lacking formal recognition as a continent—a label reserved for geological and geographic consensus—China functions continent-wide through its political and economic reach. Its administrative regions—comprising 23 provinces, five autonomous regions, four municipalities, and two Special Administrative Regions—mirror the complexity and scale of its territorial dominion.

From the snow-covered foothills of Inner Mongolia to the islands of Taiwan (claimed but not universally recognized), China’s continental identity transcends borders.

Population and Cultural Tapestry: A Human Continent

Planting a human population of over 1.4 billion on its vast landmasses defines China as not just a nation, but a living continent of cultures, languages, and histories. The population density varies dramatically: the Pearl River Delta and Yangtze River Basin support hyper-urban clusters exceeding thousands of people per square kilometer, while vast interior provinces remain sparsely inhabited. G encargado—home to over 126 million—ranks among the world’s most populous cities and exemplifies the concentration driving China’s economic engine.Yet, true to its continental scope, China’s identity is rooted in deep regional diversity. Historic provinces—such as Sichuan with its Sichuanese dialect, Guangdong known for Cantonese heritage, and Xinjiang reflecting Central Asian influences—highlight a mosaic unmatched in scale. “China is not one people, not one language, but a thousand histories woven across a single geographical front,” observes geographer Dr.

Li Wei. This cultural plurality shapes daily life, governance, and innovation across its domain.

Urbanization continues to reshape the demographic landscape.

Megacities like Shanghai and Beijing—each exceeding 20 million residents—anchor megaregions that combine industrial might with technological advancement. Meanwhile, rural hinterlands sustain agricultural traditions, minority cultures, and ancestral knowledge systems that preserve the continuity of a continental past.

Environmental and Economic Forces Shaping the Continental Power

China’s continental reach encompasses some of Earth’s most critical ecosystems and economic hubs. Its rivers—the Yangtze, the Yellow, and the Pearl—support 40% of the nation’s population and drive industrial output.The country’s geography fuels renewable energy leadership, with vast wind farms in Inner Mongolia and hydropower from the Himalayan-fed metabolic systems. Yet, this expansion brings environmental challenges: air quality in industrial zones, water scarcity in the north, and the ecological strain of one of the world’s largest coal-dependent economies. Economically, China functions as a continental engine, responsible for nearly 18% of global GDP and controlling strategic supply chains from rare earth minerals to electronic manufacturing.

Its Belt and Road Initiative further extends influence across Eurasia, echoing historical Silk Road networks but magnified by 21st-century infrastructure.

The Continental Identity: China’s Place in Global Consciousness While geologists and cartographers may distinguish continents by tectonic boundaries, China’s continental status endures as a consensus of cultural cohesion, demographic scale, and geopolitical weight. Its territory hosts key UNESCO World Heritage sites from the Great Wall to the karst pillars of Guilin, symbolizing a millennium of civilization layered across space.

Politically, regional governance reflects attempts to balance unity with diversity—from autonomous regions managing ethnic minority traditions to economic special zones testing market reforms. What makes China’s continental character unique is its synthesis of ancient heritage and modern ambition—a nation simultaneously rooted in imperial history and at the forefront of global innovation. As climate change, digital transformation, and geopolitical realignment reshape borders, China’s vast, multifaceted territory will continue to redefine what it means to span a continent.

From the formidable highlands of Qinghai to the neon grids of Shenzhen, the continent of China is not merely a place on a map—it is a dynamic, evolving force that shapes economies, ecosystems, and societies across Asia and beyond. Its geographic scope, demographic density, and cultural complexity affirm that in both geography and impact, China indeed functions as a continent unto itself.

Related Post

The Gods Beneath the Imperium: How Greek Deities Forged Rome’s Divine Legacy

World Star Rock Paper Scissors Yellow Dress Full Video YouTube: Everything You Need to Know to Master the Classic Game

Oz In Lbs: The Critical Metric That Governs Weight, Trade, and Trade Weights in Every Industry

A Surprising Tale Of Fame And Fortune