What Is Biocolonialism? Unmasking the Exploitation Hidden in Nature’s Bounty

What Is Biocolonialism? Unmasking the Exploitation Hidden in Nature’s Bounty

Biocolonialism defines a deeply troubling convergence of colonial-era power imbalances and modern bioprospecting—where biological resources and traditional ecological knowledge from biodiversity-rich Global South nations are exploited without consent or fair compensation. This shadow system transforms indigenous wisdom, ancient plant use, and genetic materials into commercial commodities, often by multinational corporations and research institutions operating with lopsided control and minimal accountability. More than a historical echo, biocolonialism is a live issue shaping global debates on equity, intellectual property, and environmental justice, demanding urgent attention from scientists, policymakers, and civil society alike.

The Origins and Rise of Biocolonial Practices

Though the term “biocolonialism” is relatively recent, its roots stretch deep into centuries of colonial extraction. For centuries, colonial powers claimed and confiscated natural resources—from spices and rubber to medicinal plants—removing them from indigenous stewardship without consent. Today, this pattern has evolved into what experts call biocolonialism: a more sophisticated but equally coercive form where bioprospecting—the search for valuable genetic and biochemical resources—is driven by advanced genomics and pharmaceutical innovation.Biocolonial practices thrive in legal gray zones where international laws lag behind scientific capability and corporate ambition. “Bioprospecting is often framed as a ‘win-win’—scientific discovery paired with ecosystem preservation—but in practice, it frequently replicates colonial dynamics,” notes Dr. Vandana Shiva, environmental activist and scholar.

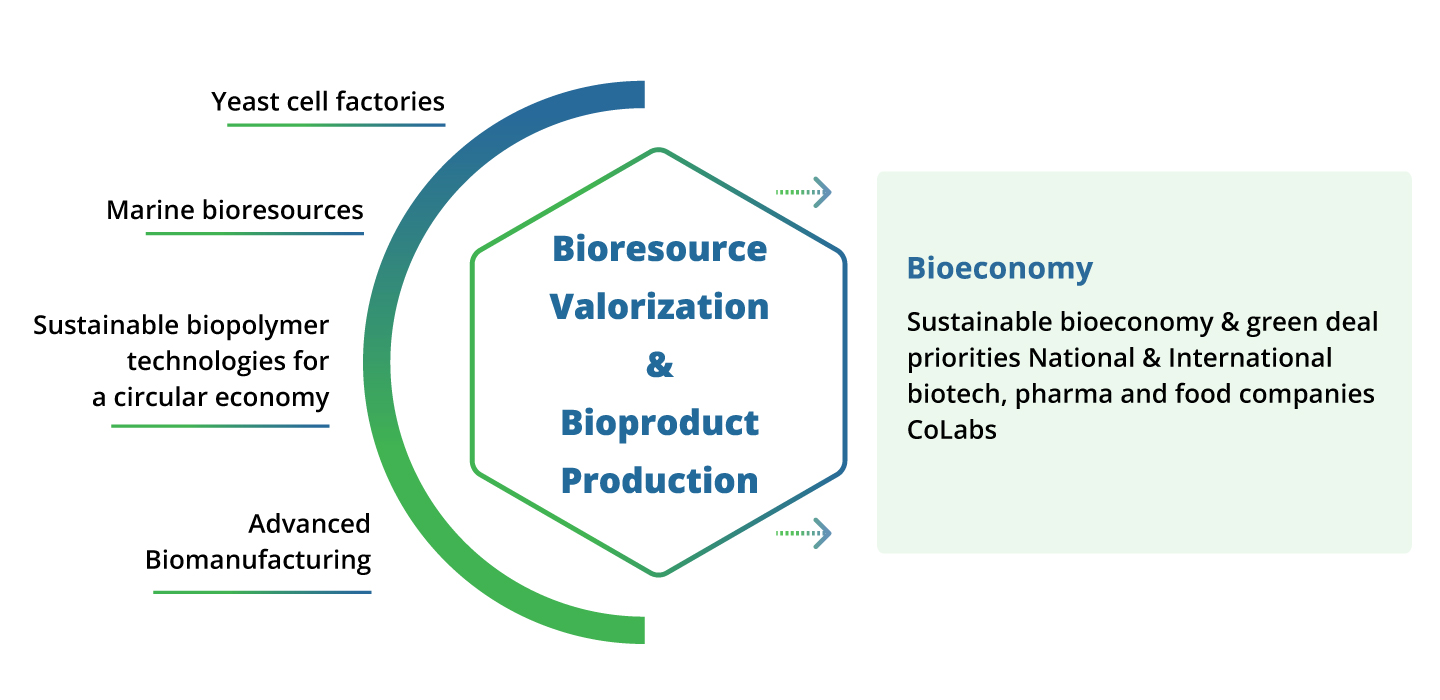

“Genetic material taken from indigenous territories is patented by distant firms, while source communities rarely benefit from profits or decision-making power.” Biological Resources and Traditional Knowledge as Targets At the core of biocolonialism lies the exploitation of two critical assets: biological materials and traditional knowledge. Indigenous peoples and local communities have conserved and managed ecosystems for millennia, developing intricate knowledge systems around plants’ medicinal, nutritional, and ecological uses. These knowledge systems, passed through generations, are increasingly targeted by biotech and pharmaceutical companies seeking novel compounds.

When researchers access plant specimens or ethnobotanical data, often under agreements lacking transparency, the risk of misuse skyrockets. “Traditional knowledge is not simply cultural heritage—it’s also practical, testable science,” explains Dr. Ramon Rotter, a biocultural rights advocate.

“Yet too often, this knowledge originates from communities and flows into patent portfolios without consent, recognition, or profit-sharing.” Biocolonial exploitation frequently bypasses international frameworks like the Nagoya Protocol, which aims to ensure fair and equitable sharing of benefits from genetic resources. “Weak enforcement and bureaucratic hurdles allow corporations to exploit legal loopholes,” warns Dr. Rotter.

“Meanwhile, original knowledge holders remain excluded from economic gains and control over how their heritage is used.”

Case Studies: Real-World Impacts of Biocolonialism

The saga of the neem tree exemplifies how biocolonial practices unfold. Native to India and widely used in traditional agriculture and medicine, neem’s pesticidal properties and health benefits attracted global attention. Multinational firms attempted to patent neem-based products, sparking international outrage.After years of legal battles, European patent offices revoked the patents, affirming that traditional knowledge cannot be monopolized. This case became a landmark in biocolonial discourse, spotlighting the clash between corporate patent strategies and indigenous intellectual sovereignty. Another case involves the rosy periwinkle, a Madagascar plant crucial in treating childhood leukemia.

While its medicinal value was integrated into global healthcare, little direct benefit reached the Malagasy people, despite their ancestral stewardship. Such patterns reinforce a broader critique: scientific advancements born from biological and cultural wealth often enrich distant economies while local communities endure environmental degradation and cultural erasure.

The economic asymmetry is stark: while pharmaceutical revenues from neem or rosy periwinkle derive from microbial sequencing, genomic patents, and synthetic derivatives, source communities rarely receive royalties or fail to access resulting medicines.

“Biocolonialism doesn’t just steal; it denies agency,” says Dr. Shiva. “It turns a people’s heritage into an asset controlled by outsiders, reinforcing historical hierarchies of power.”

The Legal and Ethical Framework Necessary to Counter Biocolonialism

International agreements like the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and Nagoya Protocol provide foundational principles—prior informed consent, fair benefit-sharing, and respect for indigenous rights.Yet implementation remains uneven, constrained by limited enforcement, uneven national legislation, and corporate resistance. Experts stress the need for binding mechanisms that hold bioprospectors accountable and empower local communities with legal representation and scientific capacity. “Bi

Related Post

Winner Of Survivor Season 33: A Deep Dive Into The Voyage That Defined A Champion

Lake Havasu City ZIP Codes: Decode Every Zip in America’s Desert Gem

Who Hurt You? Deconstructing Daniel Caesar’s "Who Hurt You?": A Clinical Analysis of Landscape of Woundedness

Where Is Boston Located: Gateway to New England’s Historic Heart