What Is a Ion? The Electrically Charged Particle Behind the Universe’s Mysteries

What Is a Ion? The Electrically Charged Particle Behind the Universe’s Mysteries

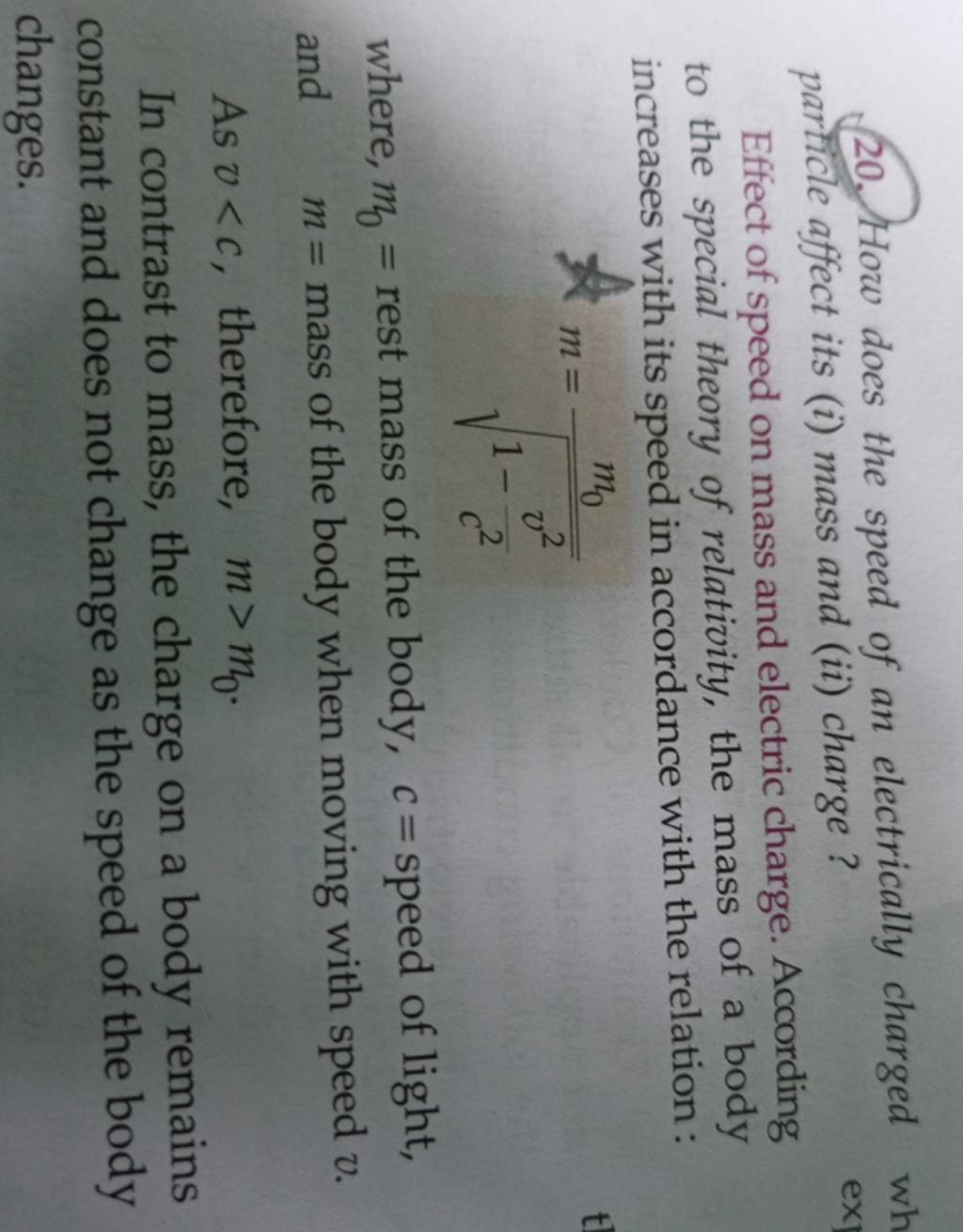

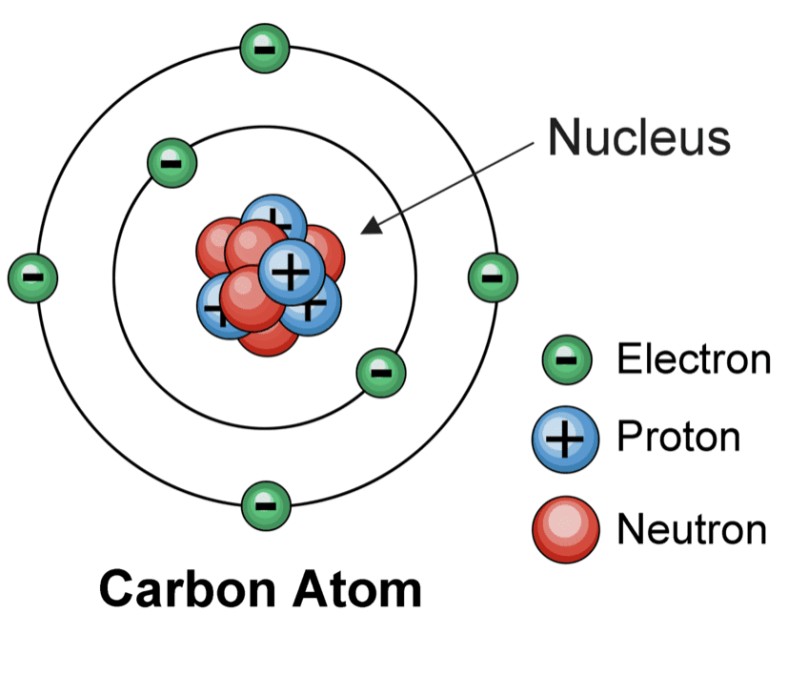

At its essence, an ion is an atom or molecule that carries a net electric charge due to the loss or gain of one or more electrons. This fundamental transformation gives ions unique behaviors that underpin much of chemistry, physics, and even biology. Whether in the air we breathe, the water we drink, or the circuits that power modern devices, ions play a silent yet indispensable role.

Understanding what defines an ion—and how it forms—is key to unlocking deeper insights into natural processes, technological advancements, and the invisible forces shaping our planet.

Each ion arises from a delicate balance shift: when an atom or molecule sheds electrons, it becomes positively charged, transforming into a cation. Conversely, when an atom absorbs an extra electron, it gains negative charge, becoming an anion.

This charge imbalance is not just a curious quirk—it defines how ions interact with electromagnetic fields, respond to other charged species, and facilitate essential energy transfers.

The Chemistry of Ion Formation

Ionization occurs through several mechanisms, with the most common being electron transfer during chemical reactions. When two substances interact—such as an acid interacting with water—electrons may shift, resulting in the formation of ions. For example, hydrochloric acid (HCl) dissociates in water: HCl → H⁺ + Cl⁻.Here, chlorine gains an electron to become a chloride anion, while the hydrogen loses its electron, forming a hydrogen cation (H⁺), which in solution behaves as H₃O⁺ due to proton solvation.

Ion formation is not limited to aqueous environments. In gases, photoionization—where photons energize atoms—creates ions high in the atmosphere.

Solar ultraviolet radiation strips electrons from molecules like oxygen and nitrogen, forming ions such as O₂⁺ and N₂⁺. These charged particles influence ionospheric conditions, affecting radio wave propagation and satellite communications.

Types of Ions: From Noble Gases to Biochemical Powerhouses

Ions are classified by charge—positive or negative—and by their origin. Cations, carrying a net positive charge, include common elements like sodium (Na⁺), calcium (Ca²⁺), and potassium, vital for nerve signaling and muscle function.Anions, like chloride (Cl⁻), sulfate (SO₄²⁻), and nitrate (NO₃⁻), play critical roles in metabolic processes and environmental chemistry.

Metals and Metals Ions: The Building Blocks of Conductivity

Metals frequently lose electrons easily, forming divalent or trivalent cations such as Fe²⁺ (ferrous), Fe³⁺ (ferric), or aluminum (Al³⁺). These ions are the charge carriers in electric currents through ionic solids and molten salts.In batteries, ion migration enables energy storage and transfer—lithium ions (Li⁺) shift between electrodes during charging and discharging. In biological systems, sodium and potassium ions establish electrochemical gradients essential for nerve impulses.

Biological Ions: The Engines of Life

Within living organisms, ions are indispensable.Sodium (Na⁺), potassium (K⁺), calcium (Ca²⁺), chloride (Cl⁻), and bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) regulate fluid balance, transmit nerve signals, contract muscles, and maintain pH. The sodium-potassium pump—an active transport mechanism—keeps cellular electrical gradients sharp, powering neurons and muscle fibers alike. Without precise ion balance, these vital functions falter, illustrating how deeply ions are woven into life’s mechanisms.

Ion Behavior in Matter and Technology

In solids, ions arrange in crystalline lattices, forming ionic compounds like table salt (NaCl) and magnesium oxide. These structures reflect strong electrostatic attractions, yielding high melting points and electrical insulation in solid form but enabling conductivity when melted or dissolved. In solutions, ions dissociate, becoming mobile charge carriers that enable chemical reactivity and electrical signaling.This mobility extends into technology: semiconductor manufacturing relies on controlled doping—introducing ionized impurities into silicon to modify conductivity. Electroplating uses ion migration to deposit metal coatings, while fuel cells depend on ion conduction through electrolytes to generate clean energy. From smartphones to spacecraft, ions operate invisibly but actively behind the scenes.

Measuring Ions: Tools of Detection and Precision

Modern science wields sophisticated instruments to detect and quantify ions.Ion-selective electrodes样 domestic saliva testing, pediatric hydration monitoring, and research-grade analyzers rely on membrane-based sensing. Spectrometry—especially mass spectrometry—identifies ions by mass-to-charge ratios, enabling breakthroughs in climate science, forensics, and biomedical diagnostics. Environmental monitoring uses ion chromatography to detect trace pollutants like nitrates in water.

These tools reveal the invisible dynamics of ion behavior—whether in ocean salinity, soil fertility, or blood chemistry—turning abstract charge into actionable data.

The Future of Ion Research: From Nanoscale to Cosmic Scales

Cutting-edge research explores ion behavior at quantum scales and cosmic distances. Ion traps and ion propulsion—used in deep-space missions—rely on precise manipulation of charged particles. In medicine, targeted ion therapies promise less invasive cancer treatments.Meanwhile, environmental scientists study storm-driven ion transport to predict pollution dispersal and climate shifts.

As technology advances, so does our appreciation of ions—not just as charged particles, but as dynamic agents shaping chemistry, biology, and engineering across scales. From powering neural impulses to driving industrial innovation, ions remain at the heart of discovery and progress.

Understanding what an ion is transcends academic curiosity; it illuminates the fundamental forces shaping matter, energy, and life.

By recognizing how atoms gain or lose electrons to become charged, we gain insight into the invisible mechanisms driving everything from a heartbeat to planetary weather patterns. In science and society, ions are far more than curiosities—they are vital players in the grand drama of natural forces.

Related Post

Palmers Funeral Home: Caring Beyond Grief, Honoring Lives with Dignity

Unveiling the Quiet Strength Behind Matt Czuchry’s Wife: A Deep Dive into Her Identity and Influence

Classroom 6x Drift Hunters: Revolutionizing Science Education with Dynamic, In-Game Experimentation

Understanding Myhisd: The Secret Lever Shaping Modern Performance Metrics