Unlocking the Hidden Primes: The Enigmatic World of Gaussian Primes in Complex Numbers

Unlocking the Hidden Primes: The Enigmatic World of Gaussian Primes in Complex Numbers

Gaussian primes—complex numbers whose prime status holds within the extended realm of ℂ that reshape mathematics’ foundational understanding of factorization. Unlike traditional primes confined to integers, Gaussian primes arise from the Gaussian integers: complex numbers a + bi where a and b are integers, and i² = −1. This extension transforms the concept of primality, revealing intricate patterns that bridge algebra, geometry, and number theory.

As mathematicians delve deeper, the mysterious properties of Gaussian primes reveal profound connections, unlocking new dimensions in both theoretical inquiry and practical computation.

At first glance, the Gaussian integers extend the integers into the complex plane, but their prime elements defy simple generalization. A Gaussian prime is a nonzero Gaussian integer that cannot be factored into a product of two non-unit Gaussian integers.

Units in this realm—1, −1, i, and −i—share multiplicative inverses but offer no structural significance in factorization. This unit classification is essential: units pose no barrier to primality, yet any prime arising as a unit multiple of another is trivial. Thus, Gaussian primes relate strictly to irreducible elements, those with no nontrivial decomposition.

“Gaussian primes are not mere curiosities—they are the natural extension of prime ideals into complex domains, offering a geometric lens on algebraic structure.” — John L. Lucas, number theorist specializing in complex arithmetic

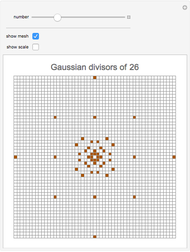

The core criterion for primality in Gaussian integers builds on size and factorization. A Gaussian integer z = a + bi is prime if its norm—defined as N(z) = a² + b²—cannot be factored further into smaller positive integers that correspond to norms of non-unit factors.

This norm interpretation links arithmetic to geometry: prime factorization in ℤ fails to capture the full story, but within ℤ[i], norms precisely track the underlying structure. For example, the rational prime 5 is not a Gaussian prime because N(5) = 25 = 5 × 5, yet it splits neatly into (2 + i)(2 − i), each with norm 5. Here, elements of prime norm remain indivisible, making 2 + i and 2 − i Gaussian primes.

This splitting behavior illustrates a profound principle: rational primes congruent to 1 mod 4 factor nontrivially into Gaussian primes, while primes congruent to 3 mod 4 remain inert—whole, unchanged, and prime. Rational primes p ≡ 3 mod 4 cannot decompose within ℤ[i]; their counterparts persist as irreducibles. Thus, the intersection of number theory and complex analysis reveals an elegant dichotomy: primes split, stay prime, or vanish—each pattern governed by modular arithmetic and the geometry of lattices in the complex plane.

Consider examples. The rational prime 2 defies intuition: N(2) = 4, and 4 = 2 × 2, yet 2 splits as (1 + i)(1 − i). But note: 1 + i has norm 2, and in fact 2 = −i(1 + i)(1 − i), showing Gaussian primes under scalar units.

In contrast, 7 ≡ 3 mod 4 stays prime, since no two integers a, b yield a² + b² = 7—impossible by modular arithmetic and sum-of-squares constraints. These behaviors map precisely onto congruence conditions, embedding deep arithmetic logic into the complex field.

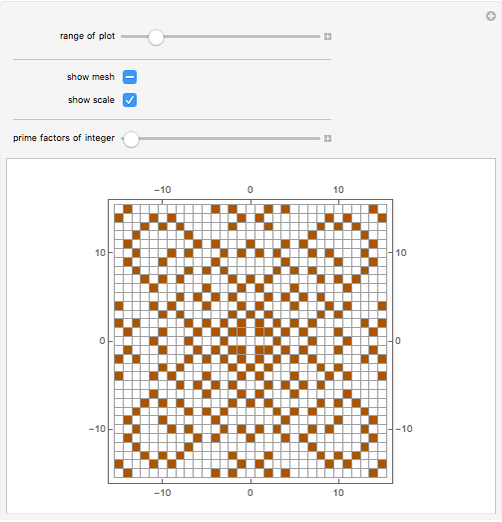

The distribution of Gaussian primes follows a lattice structure reminiscent of integer primes on the number line, yet folded across the complex plane.

Like their rational counterparts, Gaussian primes cluster in regions weighted by norms, their density influenced by prime factorization patterns and unit rotations. This spatial analogy allows mathematicians to model factoring processes geometrically, aiding both visualization and proof construction. The lattice structure supports unique theorems, including analogues of Euclid’s factorization theorem, reinforcing that Gaussian integers form a unique factorization domain.

Why This Matters Beyond Abstract Math Gaussian primes are not academic abstractions—they fuel applications in cryptography, coding theory, and quantum computing. Error-correcting codes leverage the geometry of Gaussian lattices. Quantum algorithms exploit modular arithmetic over ℤ[i] for faster factoring and discrete log computations.

Furthermore, understanding these primes deepens insights into class field theory and algebraic number fields. As technology advances, the hidden symmetries of Gaussian integers promise innovations in secure communication and computational speed.

Thus, Gaussian primes stand as a bridge between the familiar and the infinite—a testament to how complex numbers expand the frontiers of mathematical thought.

Their study challenges rote computation, inviting deeper exploration of symmetry, irreducibility, and modular logic. In mastering Gaussian primes, mathematicians do not merely expand a formula—they uncover a new language, written in complex numbers, that continues to shape both pure theory and applied practice.

What began as an elegant extension of prime ideals now pulses with mystery and utility, revealing that beauty in mathematics often lies in what remains irreducible—both algebraically and geometrically.

Gaussian primes endure not just as anomalies, but as fundamental architects of a richer, more interconnected numerical universe—one where every prime hides a complex truth, waiting to be decoded.

Related Post

MirrorGoogle On Roku: Easy Steps To Cast Your Screen with Precision

Transform Your Weekly Plans with Iheartpublix Weekly Ad — Your Key to Smart, Savvy Living

Online Globus: Revolutionizing Global Deals Through Digital Innovation

Taiwan ESIM Real Name Registration: What Travelers Must Know Before Going