Unlocking Motion: The Physics Regents Lift the Curtain on Kinematics and Dynamics

Unlocking Motion: The Physics Regents Lift the Curtain on Kinematics and Dynamics

Decoding Kinematics: The Language of Movement

At the heart of motion analysis lies kinematics—the study of displacement, velocity, and acceleration without considering their causes.

Position-time graphs

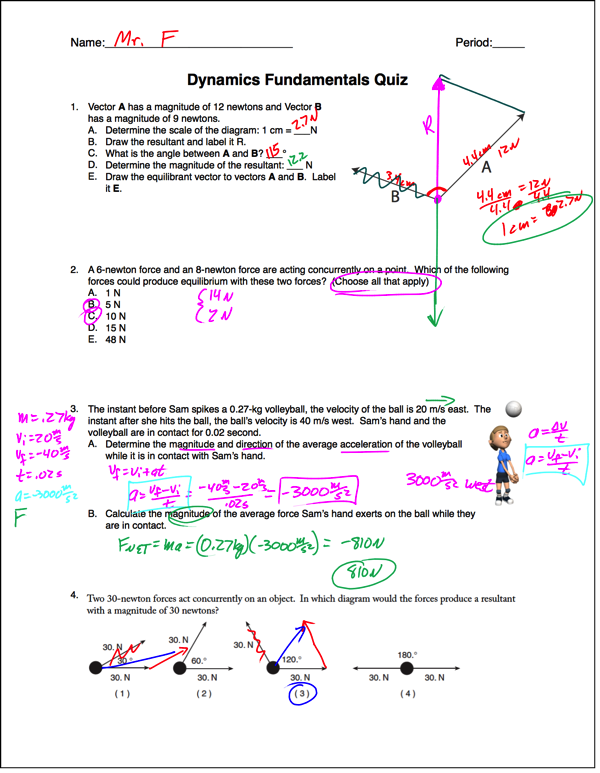

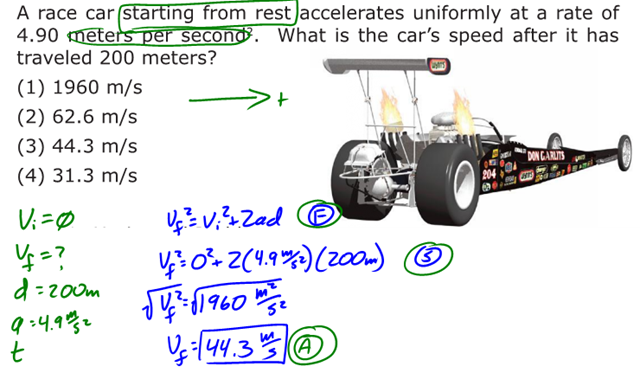

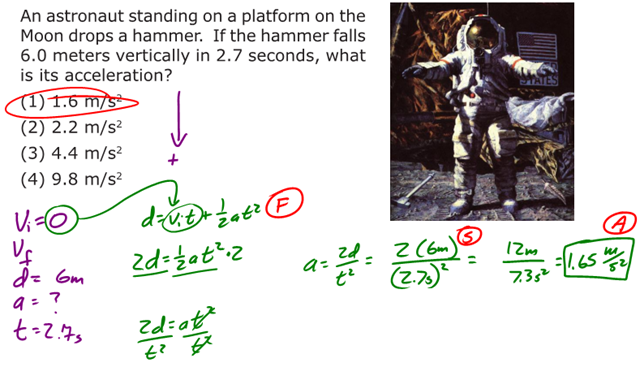

reveal how position changes over time: linear graphs indicate constant velocity, while curved lines signal acceleration. The equation \( v = \frac{\Delta x}{\Delta t} \) remains foundational—finding the average rate of change of position over time. Students often grapple with units: meters per second, kilometers per hour, and their conversions demand precision.Equally critical is the kinematic equation for uniformly accelerated motion: \[ v_f = v_i + a t \] \[ x = x_i + v_i t + \frac{1}{2} a t^2 \] These formulas allow solving real-world problems, such as determining how long a car accelerates from rest to 60 m/s when accelerating at 5 m/s²—a scenario that mirrors questions seen in recent Regents exams. Mastery here hinges on identifying knowns and unknowns swiftly, then substituting correctly.

Forces and Newton’s First: The Foundation of Change

Newton’s First Law—objects in motion stay in motion, and at rest stay at rest, absent a net force—sets the stage for understanding cause and effect in mechanics.Inertia

emerges directly: a passenger in a sudden accelerating bus lurches forward because their body resists the change in motion. But it’s Newton’s Second Law—\( F_{\text{net}} = m a \)—that quantifies force’s role. Students often encounter problems involving weight, mass, and friction: - *How much force does gravity exert on a 70 kg student?* → \( F = mg \approx 686\ \mathrm{N} \) - *What net force moves a box with 140 N of friction and 280 N of push?* → \( F_{\text{net}} = 280 - 140 = 140\ \mathrm{N} \) Graphing force vs.acceleration reveals Newton’s Third Law: every action has an equal and opposite reaction, though Regents questions typically test predictive rather than reaction-based scenarios.

Energy and Work: The Mechanics of Transfer

Energy transformations define how systems evolve under force.The work-energy theorem

states that work done on an object equals its change in kinetic energy: \( W_{\text{net}} = \Delta KE = \frac{1}{2}mv_f^2 - \frac{1}{2}mv_i^2 \).This principle powers questions on propulsion: why rocketed stages separate, or how a bungee jumper slows upon landing. Equally essential is the work formula: \[ W = F d \cos\theta \] Understanding angle dependence explains why pushing a box sideways does no work, while pushing along the direction maximizes energy transfer. Libraries of Regents problems consistently test conversion between potential (gravitational, elastic) and kinetic energy, as seen in questions about a swinging pendulum or compressed spring launching.

Rotational Motion and Torque: Beyond Linear Paths

Classical mechanics extends beyond straight-line movement into rotation.Moment of inertia

—mass distributed relative to an axis—determines rotational resistance, much like mass resists linear acceleration. Students apply \( \tau = I\alpha \) under torque \( \tau = r \times F \), where \( I = \sum mr^2 \) for rigid bodies.Rotational kinematic equations parallel linear ones: \[ \omega = \omega_0 + \alpha t \] \[ \theta = \omega_0 t + \frac{1}{2}\alpha t^2 \] Famous pendulum and wheel problems from past exams illustrate torque’s role—calculating the force at the end of a 2-meter wrench applying 50 N at 90°, producing 100 N·m torque. Angular acceleration \( \alpha = \tau / I \) becomes central when analyzing spinning disks or rotating carts.

Success in Motion: Exam Strategies and Patterns

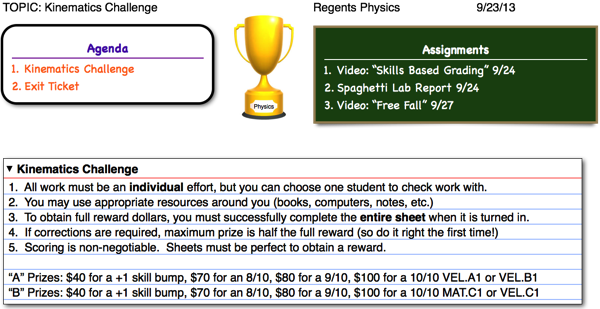

Regents success follows pattern recognition and precision.The exam consistently tests five high-yield topic clusters: - Linear and projectile motion with vector resolution - Newton’s laws with force diagrams and free-body diagrams - Work, energy, and power relationships - Rotational dynamics and torque tendencies - Graph interpretation of kinematic and energy data Step-by-step calibration is key: - Sketch freely to visualize vectors and coordinate systems - Label all knowns and unknowns clearly - Use consistent unit conversion (SI preferred) - Eliminate extraneous variables early Recent exam analyses reveal that students who break problems into substitutable components—writing equations for each phase—achieve higher accuracy.

The Physics Regents exam, far from random, rewards disciplined application of core principles across kinematics, dynamics, energy, and rotation. Mastery comes not from memorization, but from fluency in translating real-world motion into equations students master through repeated exposure to Regents-tested scenarios.

As the 2023–2024 palette shows, repetition of structured problem-solving builds the intuition necessary to anticipate, compute, and explain motion with clarity—proving that deep physical understanding transforms equation drills into true mastery.

Related Post

Understanding Fanfix Leaks: What You Need To Know

Gray Vs Silver: The Battle of the Titans in Modern Electronics Manufacturing

A Closer Look At The Intriguing Life and Legacy of Alec Wildenstein Jr., His Struggled Family, and the Unexpected Lineage of Dine and Son Lec

Old Gizzer: Reviving Precision in Analog Innovation