Unlocking Genetic Diversity: How the Law of Independent Assortment Drives Biological Variation

Unlocking Genetic Diversity: How the Law of Independent Assortment Drives Biological Variation

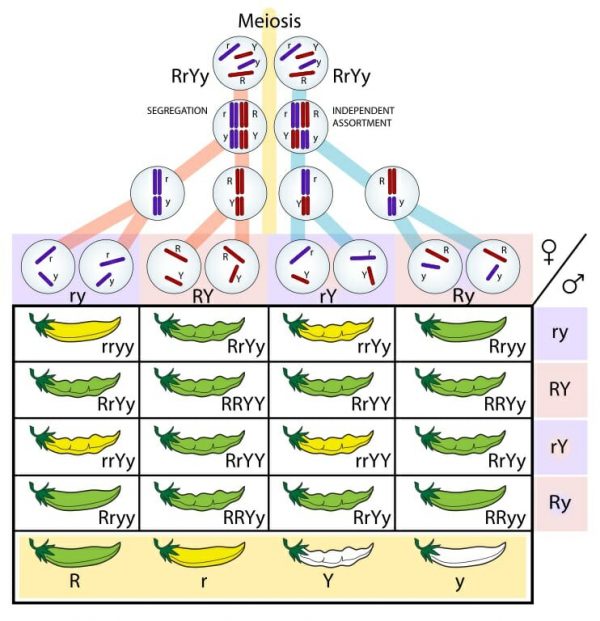

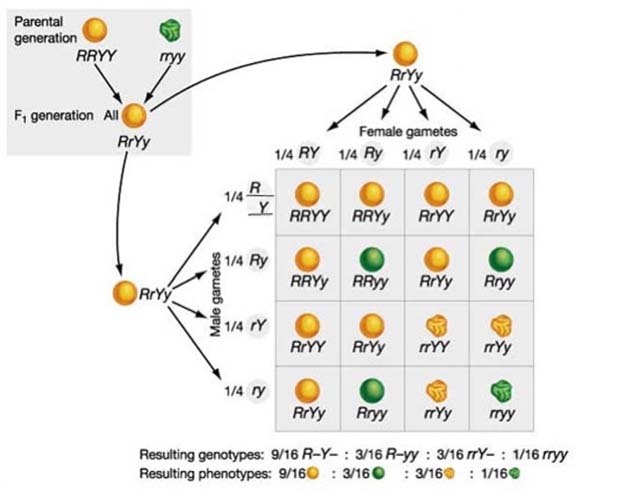

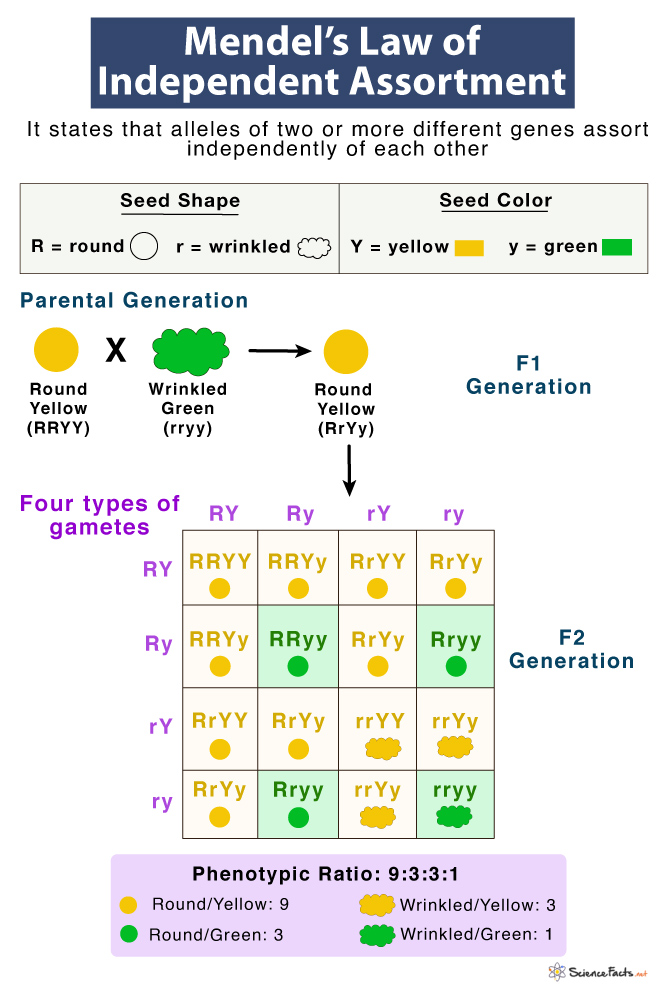

The Law of Independent Assortment, a cornerstone of classical genetics, explains how alleles of different genes segregate independently during the formation of gametes—a fundamental mechanism behind the remarkable genetic diversity seen in sexually reproducing organisms. Formulated by Gregor Mendel in the 19th century, this principle reveals how chromosomes align and separate randomly during meiosis, thus shuffling genetic material in ways that profoundly shape inheritance patterns. Unlike traits linked to a single gene, multiples of genes across different chromosomes assort independently, creating infinite combinations in offspring.

“The beauty of independent assortment lies not in predicting exact outcomes, but in understanding the sheer statistical complexity it generates,” explains Dr. Elena Marquez, a molecular biologist at the Institute of Genomic Studies. At the heart of the Law of Independent Assortment is the behavior of homologous chromosomes during meiosis I.

As cells prepare to divide, neatly paired chromosomes line up at the metaphase plate, with each pair consisting of one chromosome from each parent. Crucially, the orientation of one pair is independent of how other pairs align—a process governed by probabilistic alignment rather than deterministic logic. Each homologous pair segregates into daughter cells at random relative to one another, regardless of connections between loci on different chromosomes.

This means that the allele inherited from chromosome 1 of one parent independently influences which allele from chromosome 3 of the other parent is transmitted. This independent behavior leads to a staggering increase in genetic variability. Consider a simple model: two genes, each with two alleles (e.g., Gene A and Gene B), producing four possible allele combinations in gametes under independent assortment—AB, Ab, aB, and ab—when no linkage exists.

In reality, most genes interact across chromosomes, but even partial independence across multiple loci multiplies genetic outcomes exponentially. For diploid organisms with n pairs of chromosomes, the theoretical number of unique gamete combinations becomes 2ⁿ. In humans, with 23 chromosome pairs, this generates over eight million (2²³) potential gamete genotypes—a figure that underscores the raw potential for genetic novelty.

How Independent Assortment Fuels Evolutionary Adaptation

Independent assortment acts as a silent engine of evolution by expanding the genetic raw material upon which natural selection operates. Every sexual reproduction event, shaped by this law, produces individuals with novel allelic combinations not seen in either parent. This recombination enhances population resilience by ensuring no two offspring are genetically identical, reducing vulnerability to environmental shifts or disease outbreaks.Mechanism in Action: Allele Shuffling Across Chromosomes Each gamete receives a unique mix of maternal and paternal chromosomes due to this random alignment. For example, in corn (Zea mays), independent assortment of genes controlling kernel color, plant height, and drought tolerance during meiosis generates countless phenotypic outcomes. Variations in multiple traits emerge within a single generation, allowing rapid adaptation to changing climates or agricultural demands.

- In pea plants, Mendel observed independent assortment governing seed shape (round vs. wrinkled), color (yellow vs. green), and pod form (inflated vs.

constricted). - In fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster), gene combinations related to wing pattern, eye color, and behavior independently assort, creating phenotypic diversity critical for survival tests. - Human genetic studies confirm that regardless of parental ancestry, children inherit unique permutations of genes controlling immunity, metabolism, and morphology.

This probabilistic independence does not require physical linkage—genes located far apart or on different chromosomes assort freely, while tightly linked genes may still contribute to diversity through rare recombination events over successive generations. Beyond Simple Dominance: Independent Assortment and Complex Traits Although Mendel’s original pea experiments focused on single trait inheritance, modern genetics reveals that independent assortment profoundly influences polygenic traits—features dependent on many genes such as height, skin pigmentation, and disease susceptibility. Because these genes act in concert across tissues and life stages, their independent segregation generates a spectrum of intermediate phenotypes rather than discrete categories.

This variability enables populations to adapt gradually to selective pressures, with rare allele combinations potentially conferring survival advantages. For instance, variations in immune system genes (like MHC complex genes) assort independently, increasing a population’s ability to resist infectious diseases across generations. Similarly, metabolic pathways involving diverse enzyme-coding genes generate metabolic flexibility, vital for surviving nutrient fluctuations.

Such genetic complexity, fueled by independent assortment, forms the substrate of evolutionary innovation. Statistics Support the Power of Independent Assortment Mathematically, independent assortment follows from the principle that chromatids of different chromosomes segregate independently, with each gamete receiving one allele per gene purely by chance. For n independently assorting genes, the number of gamete genotypes possible is 2ⁿ—not a simple sum, but an exponential growth.

Mathematically, this means: - Number of gamete genotypes = 2ⁿ - Heterozygosity increases with chromosome number - Phenotypic diversity scales non-linearly with the combination of alleles inherited For humans, with 23 chromosome pairs, this results in over 8.4 million unique gametes—MoregeneticInfo.com. This vast diversity ensures no two individuals carry identical viable gametes, underpinning the genetic uniqueness of every person. Real-World Implications in Agriculture, Biomedicine, and Conservation In crop breeding, independent assortment accelerates the development of novel varieties by mixing desired traits from distantly related species or wild relatives.

Plant breeders exploit stochastic recombination to stack disease resistance, yield, and climate adaptability without repetitive inbreeding. In human medicine, understanding this law informs genetic counseling, risk assessment for inherited disorders, and personalized therapies—since disease-linked alleles on different chromosomes assort independently, altering inheritance complexity. Wildlife conservation leverages independent assortment’s role in preserving genetic variation within endangered populations.

High allelic diversity from such independent mechanisms enhances adaptive capacity, increasing long-term survival prospects amid habitat loss and climate shifts. Ultimately, the Law of Independent Assortment is not merely a genetic rule—it is a dynamic force shaping life’s richness. By enabling unpredictably varied inheritance, it fuels biological innovation across ecosystems, underpins evolutionary success, and enriches the tapestry of life with every reproductive cycle.

As researchers continue to decode genetic complexity, this foundational principle remains essential, illuminating how randomness at the chromosomal level spawns orderly diversity.

Related Post

Is Reuters News Truly Reliable? Separating Fact from Perception in Global Journalism

Why Gmail Business Email Is the Untapped Engine of Executive Productivity

Free Legal Voices in the Heart of New York: How Pro Bono Lawyers Change Lives

Unlock Retro Gaming: Mastering PSP Emulators for Flawless Emulation