Transforming Lives: The Shifting Tides of Planned Change in Social Work Practices

Transforming Lives: The Shifting Tides of Planned Change in Social Work Practices

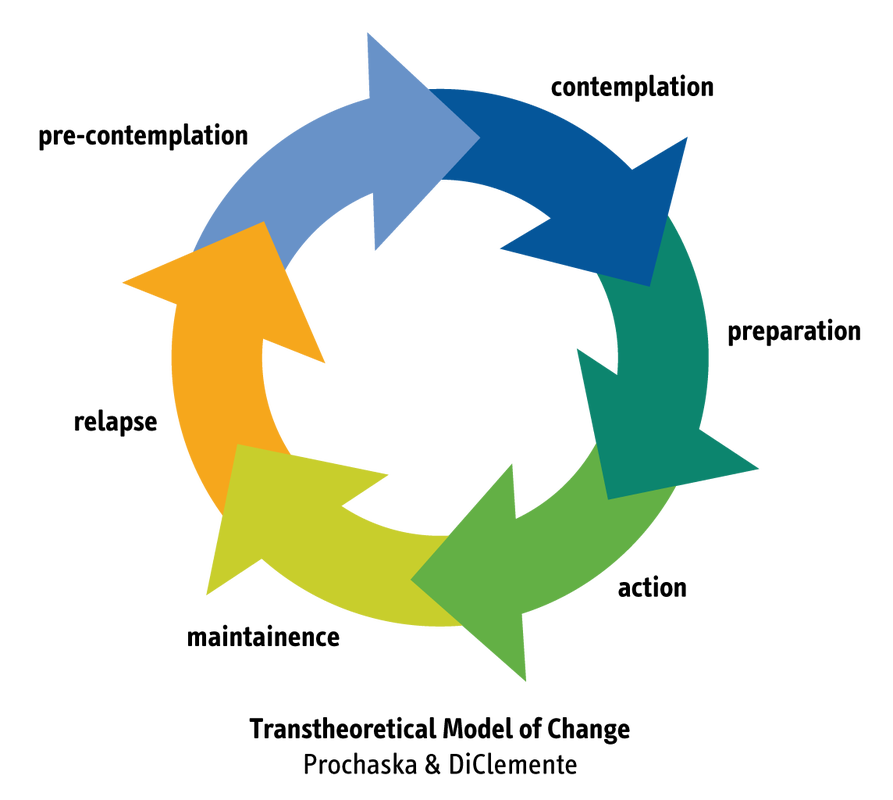

When social workers confront complex human challenges—poverty, trauma, family breakdown, systemic inequity—they increasingly rely on structured transformation. The Planned Change Process in social work offers a deliberate, evidence-based framework to guide clients from crisis toward stability and empowerment. This method, rooted in systematic assessment, collaborative goal setting, and iterative evaluation, bridges the gap between intervention and lasting impact.

Unlike reactivity or ad-hoc support, planned change prioritizes intentionality, ensuring that every step is not only compassionate but strategically aligned with measurable outcomes. As social work evolves in response to shifting societal needs, understanding and implementing this process has become critical to effective practice.

The Core Principles of Planned Change in Social Work

Planned Change in social work centers on a cyclical, four-phase process designed to empower clients as active agents in their own transformation.At its heart lies a structured yet flexible approach: assessing current realities, identifying desired futures, designing actionable steps, and evaluating progress with ongoing adaptation. This framework responds to the fundamental insight that meaningful change requires both individual readiness and systemic support. Central to the process are key principles: - **Client-centered assessment**: Comprehensive evaluations that capture the client’s strengths, barriers, cultural context, and lived experiences form the foundation.

As social workers ask, “What matters most to you?” they shift from prescriptive solutions to partnership-based planning. - **Collaborative goal setting**: Goals are not imposed but co-constructed, ensuring commitment and relevance. Research shows that when clients help define objectives—such as securing stable housing or improving mental health—motivation and self-efficacy increase significantly.

- **Incremental intervention design**: Rather than overwhelming clients with sweeping reforms, change is broken into manageable steps. This incremental approach accommodates fluctuating circumstances and builds momentum over time. - **Ongoing evaluation and feedback loops**: Continuous data collection and reflective practice ensure that strategies remain effective and responsive.

This adaptive rhythm prevents stagnation and supports real-time adjustments. “The strength of planned change lies in its balance of structure and flexibility,” notes Dr. Elena Marquez, a senior social work researcher.

“It respects the client’s journey while keeping focus on measurable, meaningful progress.”

Phase 1: Assessment – Mapping the Starting Point

Comprehensive assessment serves as the compass for the entire change process. Without a clear understanding of the client’s environment, challenges, and aspirations, interventions risk misalignment and inefficacy. Assessment integrates multiple dimensions: personal history, social supports, mental and physical health, economic status, and environmental stressors.Social workers employ tools such as: - In-depth interviews to explore lived experiences and perceptions - Standardized screening instruments for trauma, substance use, or risk factors - Community resource mapping to identify existing supports and gaps - Cultural and contextual analyses to ensure strategies are culturally responsive This phase challenges practitioners to listen deeply, avoid assumptions, and recognize structural inequities that shape client realities. For example, a family struggling with homelessness may face not only economic hardship but also discrimination in housing systems—a reality requiring both individualized case management and advocacy. Planned change emphasizes that assessment is not a one-time task but a dynamic process, recurring throughout intervention.

As circumstances evolve, so too must the understanding of what change requires.

Phase 2: Collaborative Goal Setting – Shared Vision, Shared Power

Once the assessment clarifies needs and strengths, the next critical step is collaborative goal setting. This moment marks a turning point where clients transition from passive recipients to co-architects of their futures.The focus shifts from “What should we do?” to “What matters most for you—and how can we build it?” Effective goal setting follows a specific pattern: - Specific and behaviorally defined objectives (e.g., “Attend job readiness workshops twice monthly” vs. “Get a job”) - Time-bound milestones that create urgency and track progress - Alignment with client values and strengths to sustain motivation - Inclusion of both short-term wins and long-term aspirations Research in community social work demonstrates that goals co-created with clients yield 37% higher achievement rates than those prescribed by practitioners alone. This success stems from elevated ownership and emotional investment.

Consider Maria, a formerly incarcerated client engaged through a community-based reintegration program. Through guided dialogue, she articulated two key goals: securing stable housing within six months and regaining custody of her children. The social worker helped map concrete steps—reserving transitional apartments, applying for housing vouchers, and attending parenting classes—transforming abstract desires into actionable pathways.

“This isn’t about technicians delivering services,” says participatory practice advocate Jamal Carter. “It’s about creating shared purpose. When clients articulate their own vision, they activate inner resources most external interventions can’t reach.”

Goal setting also incorporates resilience-building.

By celebrating small victories, clients develop confidence—critical for navigating setbacks common in social challenges. Each milestone reinforces the belief that change is possible and within reach.

Phase 3: Implementation – Building Momentum Through Strategic Interventions

With goals in place, the planned change process moves into intervention implementation—a phase defined by structured yet adaptable actions. Social workers deploy targeted strategies tailored to identified priorities, often combining direct services, system navigation, and community collaboration.Common interventions include: - Case management to coordinate housing, healthcare, and legal aid - Psychoeducation to build coping skills and mental resilience - Access to transportation, childcare, or housing subsidies to reduce barriers - Peer mentoring and support groups for social connection and shared learning - Advocacy within systems such as schools, courts, or healthcare providers Integration across domains ensures holistic support. For instance, supporting a youth experiencing homelessness requires not only securing shelter but also connecting with educational programs, mental health services, and employment prep. Technology is increasingly shaping implementation.

Digital case management platforms, remote monitoring tools, and telehealth services extend reach—especially in underserved areas—while data dashboards help track progress in real time. Yet, human connection remains essential: consistent, empathetic relationship-building fosters trust and continuity even amid technological advances. A key innovation in implementation is trauma-informed practice.

Recognizing that many clients have endured significant trauma, interventions prioritize safety, choice, and empowerment. This approach prevents re-traumatization and promotes healing-centered engagement, aligning discipline with dignity.

Phase 4: Evaluation and Adaptation – Closing the Feedback Loop

Planned change rejects the myth of a “set-and-forget” process.Evaluation is both a formal checkpoint and an ongoing reflection, enabling timely adjustments to enhance effectiveness. Social workers collect quantitative data—attendance rates, housing stability, employment outcomes—and qualitative insights through client feedback, focus groups, or narrative reflections. Critical evaluation questions include: - Are we advancing toward the defined goals?

- What barriers are emerging? - How are clients perceiving their progress and well-being? - What refinements improve engagement or outcomes?

Data-driven adjustments may involve redefining goals, modifying strategies, or reallocating resources. For example, if a job training program shows low participation, the team might expand outreach, offer childcare support, or adapt curriculum based on client preferences. Research consistently links regular evaluation in social work to improved client outcomes and program accountability.

As Dr. Nia Okafor, lead evaluator at the National Institute for Urban Social Policy, emphasizes: “Change isn’t finished when a plan ends. It’s lived through continuous learning.” Practical examples of adaptive evaluation include: - Monthly check-ins with clients to gather real-time feedback - Quarterly reviews by interdisciplinary teams to refine intervention models - Local benchmarking against regional best practices This dynamic responsiveness ensures that services remain relevant and impactful, especially in rapidly changing or crisis-prone environments.

Challenges and Considerations in Applying Planned Change

Despite its strengths, implementing the planned change process faces notable challenges. Time constraints and high caseloads can pressure practitioners to streamline phases, potentially sacrificing depth. Cultural and linguistic gaps may obscure assessment accuracy, requiring intentional investment in cultural competence and bilingual resources.Systemic barriers also hinder progress. Fragmented services, underfunded programs, and bureaucratic red tape can disrupt even the most carefully planned interventions. Social workers often advocate their clients across siloed institutions—housing agencies, courts, healthcare systems—navigating complexity with resilience.

Equally vital is maintaining ethical fidelity. Planned change must balance structure with flexibility, avoiding rigid protocols that override individual dignity or context. Continuous training and supervision help practitioners uphold core values: respect, empowerment, and social justice.

Moreover, equity must be central. Historically marginalized populations—people of color, LGBTQ+ individuals, people with disabilities—face compounded barriers. Effective planning demands proactive inclusion of these voices in goal setting and strategy design, ensuring change is not just efficient but just.

Overcoming these challenges requires organizational commitment—adequate staffing, training, technology, and policy support. When systems empower practitioners to apply planned change thoughtfully, transformative outcomes become not just possible, but sustainable.

Planned Change as a Catalyst for Sustainable Social Impact

The Planned Change Process in social work represents more than a methodology; it embodies a philosophy centered on purposeful, collaborative transformation. By grounding practice in assessment, co-created goals, strategic intervention, and adaptive evaluation, social workers move beyond temporary fixes toward lasting change.This structured yet humane approach strengthens client agency, enhances service efficacy, and fortifies community resilience. As social challenges grow more intricate, the discipline demands nothing less than intentional, accountable change—one step at a time, guided by insight and compassion. In embracing planned change, social workers honor both the complexity of human lives and the profound responsibility to lead meaningful, lasting improvement.

Related Post

The Atomic Language of B: Decoding Chemical Bonds Through Lewis Dot Structure

Florida Governor Election 2024: All You Need to Know as the State Heats Up

Michelle Randolph Husband Emerges as a Trailblazer in Modern Advocacy and Community Leadership

The Dispossessed Yell: How Pentecost’s Ford Pinto Echoes the Grief in *The Outsiders*