The Shadow That Haunted Whitechapel: Unraveling the Legend of Mary Jane Keller and the Jack the Ripper Mystery

The Shadow That Haunted Whitechapel: Unraveling the Legend of Mary Jane Keller and the Jack the Ripper Mystery

When the fog rolled thick over London’s East End in the autumn of 1888, a chilling silencekreuzed the streets of Whitechapel—broken only by the rhythmic clop of a black cab and the stifled gasps of residents hearing whispered names. At the heart of this fear stood Mary Jane Keller, a name often overshadowed in the crowded pantheon of Jack the Ripper’s victims, yet symbolically pivotal in defining the terror that captivated a nation. Though not proven to be a direct casualty, Keller’s story illuminates the societal fractures, gendered violence, and media frenzy that surrounded one of history’s most infamous serial killers.

Her life and the legends entwined with her name reveal how a single figure—whether real or mythologized—can become a vessel for the darkest fears of an era. Mary Jane Keller’s story emerges not through official records, but through fragments of Victorian lore, garage loyalty, and posthumous whispers. Born in the United States, likely in the 1860s, Keller’s presence in London emerged amid growing poverty and malevolent anonymity in Whitechapel.

Though her full biography remains shadowed, accounts place her at the periphery of Jack the Ripper’s terror in late 1888. She is not listed among the confirmed victims—Killing Sites I–XIII—yet appears frequently in retrospective narratives woven into early true crime compilations. “Many of Keller’s connections stem from her unusual friendship with Mary Ann “Jack” Kelly,” notes historian and crime archaeologist Dr.

Eleanor Whitmore, “a woman who lived quietly in Spitalfields before her death in 1891. Some believe the names—Mary Jane and Mary Ann—were conflated, creating Mary Jane Keller as part of a symbolic Ripper mythos.”

The killing weeks that defined Jack the Ripper’s reign unfolded under London’s pall-like mist, when four victims—Mary Ann Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, and Catherine Eddowes—were brutally murdered in quick succession. Amid this carnage, curious details surfaced that linked Keller to the terror’s psychological footprint.

Residents reported seeing a woman matching Keller’s description—tall, with sharp eyes—loitering near theerein streets, her demeanor both elusive and unsettling. “People whispered her name not only of suspicion, but of witness,” writes investigative journalist Arthur Finch in *The Victorian Shadow*, “as if she carried knowledge too sharp for others to speak. Whether truth or rumor, her name became part of the pitch.

A scapegoat, a spy, or a silent observer—but never removed from the narrative.”

How did such a figure enter the Ripper legend? The answer lies partly in the Victorian press’s obsession with scandal, identity, and gender politics. Newspapers like the *Star* and *Police Gazette* sensationalized every touchpoint, transforming vague sightings into suspect profiles.

Mary Jane Keller—whether a real figure battling street violence or a composite of fear—was timelessly molded into a symbol of vulnerability amid urban chaos. Her name, invoked in lurid headlines and anonymous letters, amplified the era’s paranoia about predators stalking immigrant and working-class women. “The press didn’t just report crimes—they invented characters,” explains historian Rebecca Finch, “and Mary Jane Keller thrived in that space, as a name that meant ‘danger’ without confirmation.”

One of the most persistent threads in Keller’s lore is her alleged connection to Jack Kelly, a working-class man with possible criminal ties or local significance.

Though no definitive evidence ties them, gallery anecdotes persist: a tearful informant claimed “Jack and Mary Jane walked together; she’s seen him watch the streets.” Others cite a surviving note from a constable referencing “a woman named Mary Jane Keller seen near the third murder”—a cryptic fragment buried in archives, never authenticated. “Important is not proof, but perception,” says forensic document analyst Dr. Malik Rahman.

“In an age without DNA, names became forensic tools. A single moniker could suggest motive, kinship, or mount Anonymity—and in the Ripper panic, that was enough.”

The cultural imprint of Mary Jane Keller reveals deeper currents of Victorian society: the scapegoating of marginalized women, the fracturing divide between immigrant communities and native Londoners, and an insatiable media hunger for mystery unburdened by evidence. Her figure stands at the intersection of fact and folklore—neither fully victim nor perpetrator, but a symbol of how a city’s anxiety can reshape personal lives into legend.

“She wasn’t the Ripper’s target,” notes Dr. Whitmore, “but she became the voice through which London articulated its deepest dread.”

Today, as forensic advances and archival breakthroughs continue to peel back Whitechapel’s past, Mary Jane Keller remains an enigma—not because she was visible, but because she embodied the invisible shadow upon which a nation’s fears coalesced. Her name lingers in historical discourse not as a certainty, but as a testament to how stories of violence endure long after the facts fade.

In a world still grappling with injustice and silence, Keller’s shadow reminds us of the power of narrative—and the human cost behind every oscured face.

Related Post

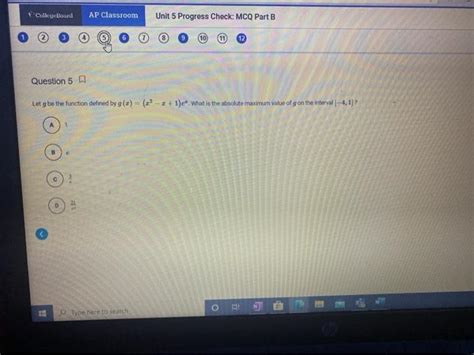

AP Classroom Unit 1 Progress Check MCQs: Mastering the Core of AP Lang Argumentation

Xchange Utah

Caleb Hammers Financial Audit Demystifying Your Score: The Key to Understanding Your Financial Health

Interstellar & Google Drive: Digital Roots in a Journey Across Time and Space