Peninsulares Defined: The Colonial Elite Who Shaped Spanish America

Peninsulares Defined: The Colonial Elite Who Shaped Spanish America

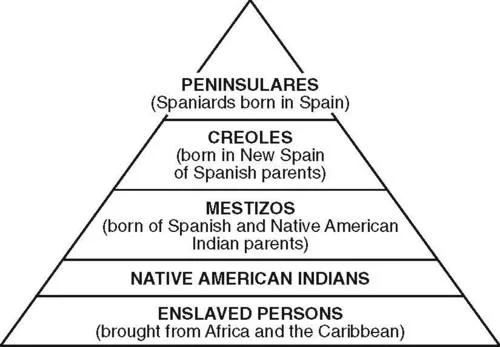

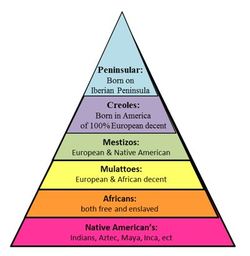

Long before "criollos" or "mestizos" defined colonial identities in Spanish America, a distinct group emerged at the heart of empire: the Peninsulares. Born in the Iberian Peninsula and transplanted to the Americas, these elite peninsular-born officials wielded unprecedented political, economic, and social power during the age of empire. Their role was not merely administrative—it was foundational to how Spain governed its vast colonial domains, shaping policies, exploiting resources, and defining identities across centuries.

The Roots of the Peninsulares in Spanish Colonial Rule

The term *Peninsular* refers specifically to individuals born in the Iberian Peninsula—Spain and Portugal—who held authority in the overseas colonies.

Matchless in their privileged status, they occupied the apex of colonial hierarchy, a system formally entrenched by the Spanish Crown’s rigid social stratification. From the earliest colonial ventures in the 16th century onward, Peninsulares dominated key posts: audiencias, viceroys, detailed, and royal courts, immune to exclusion by local-born elites regardless of wealth or influence.

As historians définitively note, “Peninsulares were not just settlers—they were the operating class of empire,” reinforcing their claim to primacy. This structural advantage stemmed from Spanish Crown policy, designed to chain political and economic power to the metropole.

Their presence ensured that critical decisions affected the colonies flowed back to officials born in Spain—architects more aligned with Madrid’s interests than distant settler communities.

Political and Administrative Dominance

Peninsulares controlled the spine of colonial administration: • They filled the highest judicial and executive roles, including supreme audiencias (regional supreme courts) and viceregal governments. • The Council of the Indies in Madrid, composed entirely of peninsular-born officials, directed all colonial governance from Spain. • They monopolized key bureaucratic posts, excluding creoles and mestizos from meaningful influence.

• This centralization enforced imperial loyalty but fostered resentment among local elites who resented external control.

“The Crown’s reliance on peninsular officials was deliberate,” explains historian Felipe Fernández-Armesto. “It minimized risks of rebellion by ensuring authority remained loyal to the throne.” Yet this system also deepened cultural divides between the colonial-born elite and those of mixed or purely American origin.

Economic Control and Resource Extraction

Beyond governance, Peninsulares directed the flow of wealth from the Americas back to Europe, overseeing the extraction of silver, gold, and agricultural surpluses that fueled Spain’s global power. Key economic levers included:

- Oversight of the Casa de Contratación in Seville, which monopolized colonial trade and regulated shipping of precious metals.

- Supervision of mining operations in Peru’s Andes and Mexico’s central highlands, where crown-licensed peninseditary companies dominated extraction through encomiendas and later haciendas.

- Control of fiscal systems that funneled colonial revenues to Madrid, financing wars, infrastructure, and imperial prestige—at the expense of local development.

“Colonial economies thrived only through peninsular direction,” argues economic historian María Luisa García.

“Their profit motives prioritized extraction over sustainable growth, entrenching dependency.”

Cultural Identity and Social Hierarchy

Peninsulares cultivated an identity sharply distinct from the American-born and mixed populations. They viewed themselves as bearers of Spanish civilization, often dismissing local cultures as ‘barbaric’ or ‘uncivilized.’ Their social prestige rested on birthright, educational ties to European institutions, and adherence to Catholic orthodoxy enforced through religious orders like the Jesuits and Franciscans.

While creoles—American-born Spaniards—often held local influence and wealth, they remained second-class under peninsular rule. This exclusion nurtured simmering tensions, as creole elites resented penalties like higher taxes, limited access to senior posts, and eran barred from the highest state offices.

The resulting social fracturing laid fertile ground for independence movements decades later.

Education, Religion, and the Consolidation of Power

Access to elite institutions reinforced peninsular dominance. Universities such as Salamanca and Santo Tomás in Seville trained peninscular administrators, ensuring a loyal cadre cradled in Spain’s intellectual traditions. Religious orders, deeply intertwined with colonial governance, further cemented control

Related Post

Peninsulares Defined: The Spanish Elite Who Shaped Colonial Latin America

Streamline Your Ohio License: Mastering State BVE Online Services

Quantity Effect: How Volume Transforms Economic Power and Consumer Behavior

Who Owns Instagram? Unveiling the Corporate Architecture Behind the World’s Most Visual Platform