Osmosis Defined: The Silent Diffusion That Powers Life and Engineered Systems

Osmosis Defined: The Silent Diffusion That Powers Life and Engineered Systems

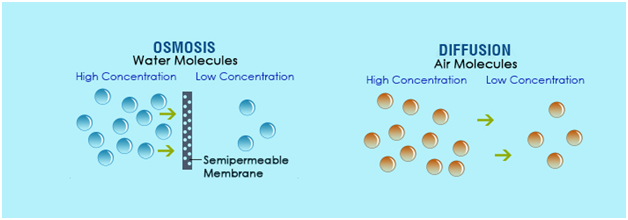

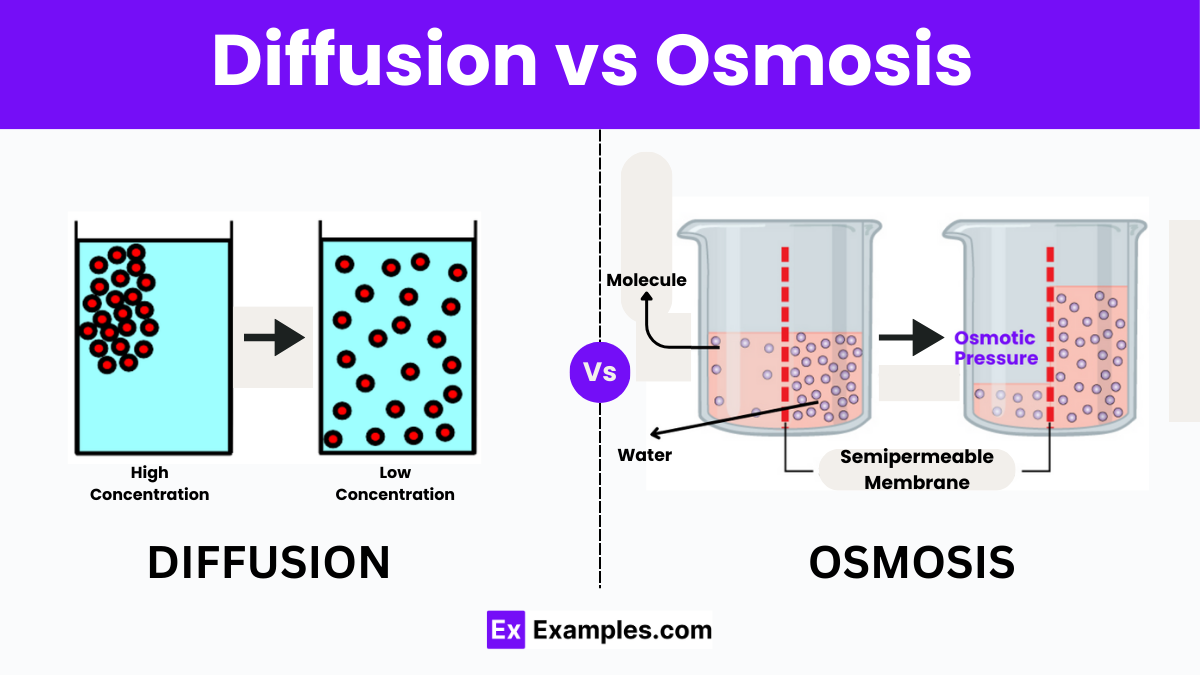

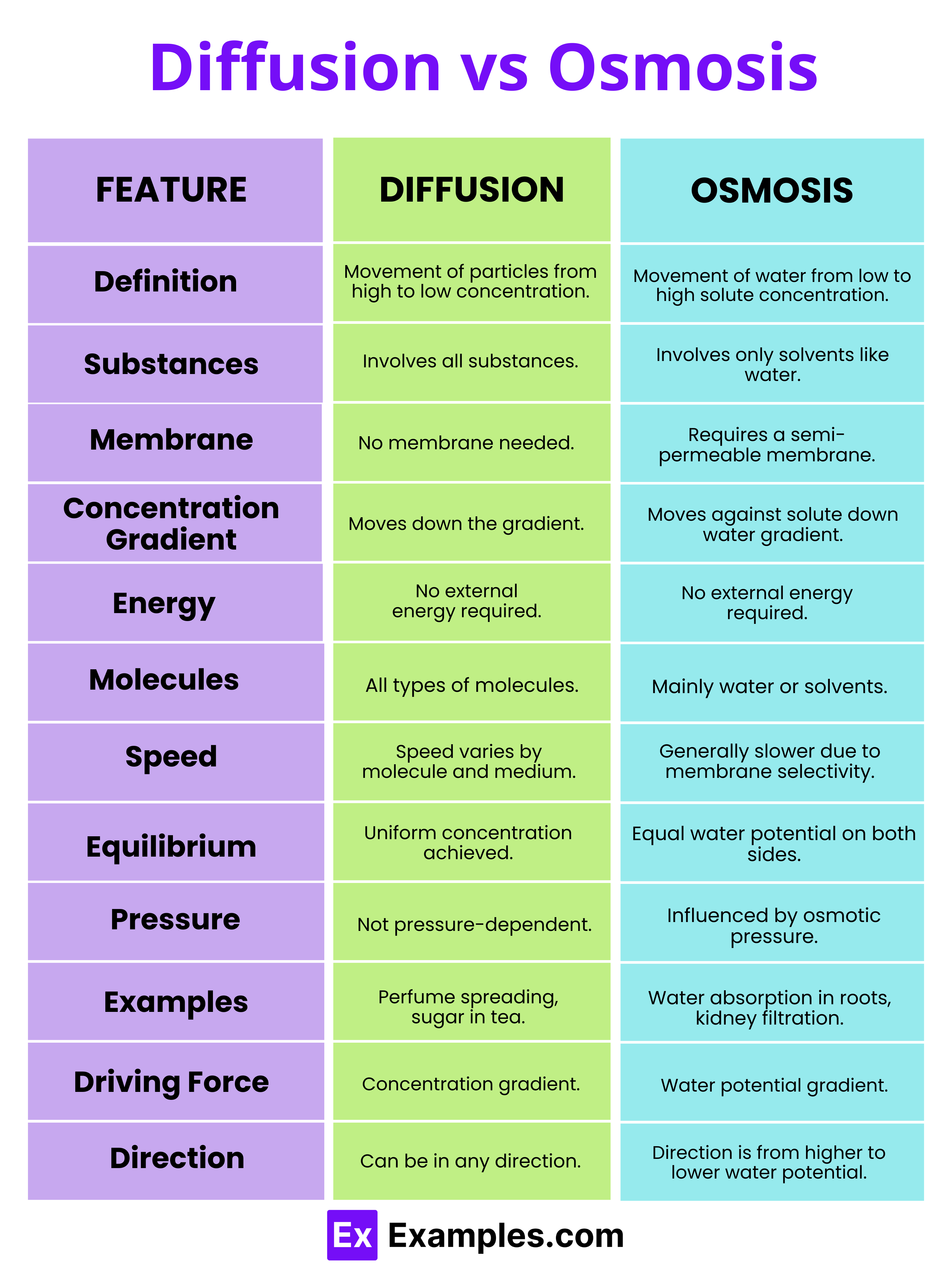

Osmosis, the passive movement of water across a semipermeable membrane from a region of low solute concentration to high solute concentration, stands as one of the most fundamental transport mechanisms in biology and chemical engineering. This subtle yet powerful process governs cellular hydration, nutrient absorption, and even large-scale industrial filtration. Understanding osmosis not only reveals nature’s elegant design—in cells and organs—but also underpins breakthrough technologies from desalination plants to advanced drug delivery systems.

Through detailed mechanisms and real-world applications, this article unpacks osmosis with precision, clarity, and scientific rigor.

The Core Mechanism: How Osmosis Drives Molecular Flow

At its biological heart, osmosis is defined by a precise physical principle: water molecules diffuse through selectively permeable membranes in response to osmotic gradients. The membrane allows only water—or small, uncharged molecules—to pass, excluding ions and larger solutes.When two solutions with different solute concentrations are separated by such a barrier, water flows to equilibrate solute levels, reducing the concentration difference over time. Key factors shaping osmosis include: - **Osmotic Pressure**: The force exerted by solute concentration differences, expressed in warranty pressure units (e.g., atmospheres or millimeters of mercury). - **Membrane Permeability**: The ability of the barrier to selectively allow water passage, often described by hydraulic conductivity.

- **Temperature Influence**: Higher temperatures increase molecular kinetic energy, accelerating osmotic flow rates. The equation governing osmotic pressure (π) in dilute solutions, as formalized by Van’t Hoff, reflects this relationship: π = iMRT where *i* is the van’t Hoff factor, *M* the molar concentration, *R* the gas constant, and *T* the absolute temperature. This equation quantifies how solute concentration directly drives water movement.

In cells, osmosis maintains turgor pressure in plant cells—critical for rigidity and structural support—while regulating ion balance in kidney tubules to prevent dehydration. Disruptions in osmotic equilibrium, such as in kidney failure, can lead to severe physiological imbalances, underscoring osmosis’s life-sustaining role.

Engineering the Flow: Osmosis in Industrial and Technological Applications

Beyond biology, osmosis forms the working principle behind reverse osmosis (RO)—a cornerstone of modern water purification and desalination.By applying external pressure greater than natural osmotic pressure, RO forces water through a synthetic membrane, leaving salts and contaminants behind. This technology now supplies drinking water to over 300 million people globally, transforming arid regions and water-scarce cities. Other engineered uses highlight osmosis’s versatility: - **Reverse Osmosis Desalination**: Converting seawater into potable water by overcoming natural osmotic gradients, producing up to millions of liters daily.

- **Forward Osmosis**: A variant that leverages natural water gradients to purify wastewater or concentrate food and pharmaceuticals without high-pressure pumps. - **Wastewater Treatment**: Membrane bioreactors use osmotic principles to recover clean water from industrial effluent, reducing environmental discharge. In drug delivery, osmosis powers osmotic pumps—controlled release systems that use fluid pressure from osmotic gradients to deliver steady medication doses, a breakthrough for chronic disease management.

Real-world systems exemplify osmosis’s impact: - Israel’s Sorek Desalination Plant, one of the world’s largest RO facilities, processes over 600,000 cubic meters of seawater daily using optimized osmotic pressure management. - In space exploration, osmotic processes help recycle astronaut urine into drinking water aboard the International Space Station, demonstrating closed-loop sustainability. Osmosis thus bridges nature’s design and human innovation, enabling both the survival of living organisms and the advancement of sustainable technology.

Real-World Biological Examples: Life Depends on osMotic Balance

In plant physiology, osmosis directly governs how roots absorb water from soil. Soil water potential—affected by dissolved salts, temperature, and atmospheric demand—drives root cell hydration. When soil becomes too saline, osmotic stress limits water uptake, wilting plants despite adequate moisture.This phenomenon explains why crops fail in saline soils, emphasizing osmosis as a target for agricultural adaptation through salt-tolerant breeding and irrigation management. Animal cells face similar challenges. Red blood cells in hypertonic solutions shrink (crenation), while those in hypotonic environments swell and may burst (hemolysis).

The human body tightly regulates blood osmolarity via kidneys, hormones like antidiuretic hormone (ADH), and thirst mechanisms—all calibrated to preserve cellular osmotic balance.

Real-World Technological Examples: Scaling Osmosis for Global Challenges

Modern global water security increasingly relies on osmotic technologies, especially reverse osmosis. When seawater’s osmotic pressure exceeds 26 atmospheres—roughly equivalent to the pressure needed to reverse natural flow—RO systems become essential.These plants now supply complex urban infrastructures, including Dubai and Singapore, where natural freshwater is scarce. Emerging innovations expand osmosis’s reach: - **Forward Osmosis Membranes**: Enabled by advances in nanotechnology, these membranes harness natural osmotic differences using “draw solutions,” reducing energy use compared to high-pressure RO. - **Osmotic Power Generation (Pressure Retarded Osmosis)**: Turbines harness energy from salinity gradients between freshwater and seawater—potentially a renewable source rivaling tidal and solar.

- **Microfluidic Osmoregulation Devices**: Lab-on-a-chip systems use controlled osmotic gradients to manipulate biological samples, driving miniaturized diagnostics and synthetic biology testbeds. These applications reveal osmosis not as a passive process, but as an active lever for innovation in health, energy, and sustainability. Osmoregulation in extreme environments further illustrates nature’s mastery.

Desert beetles concentrate water vapor via hydrophilic surfaces that exploit osmotic gradients, while deep-sea organisms maintain internal pressure balances against crushing external forces—each example reinforcing the centrality of osmotic principles.

Conclusion: Osmosis as the Intrinsic Engine of Life and Progress

From turgid plant cells to desalination plants, osmosis operates as science’s silent architect—steering fluid movement across boundaries without active energy. Defined as the passive diffusion of water driven by solute concentration gradients, its mechanism balances ecosystems and enables human ingenuity.Real-world applications—spanning medicine, agriculture, and sustainable infrastructure—demonstrate how harnessing osmosis addresses critical challenges from water scarcity to chronic illness. As research deepens understanding of membrane dynamics and gradient engineering, osmosis remains not just a scientific concept, but a vital key to a resilient future. Understanding its definition, mechanisms, and global impact is essential for anyone invested in life’s sustainability and technological evolution.

Related Post

Roblox Script Executor: The Only 2024 Guide to Builder-Grade Game Logic You Need

Talkshow Reveals How Public Figures Shape Truth – The Unseen Power Behind Live Media Conversations

The Rise of Sahbabii Real Name: From Sahbabii to Hip-Hop Sensation on FM Legend

RaquelPedraza Redefines Public Advocacy: How One Voice Shapes Global Discourse