If the Residual Is Negative, Is It Really an Underestimate? Unpacking Residual Analysis in Forecasting

If the Residual Is Negative, Is It Really an Underestimate? Unpacking Residual Analysis in Forecasting

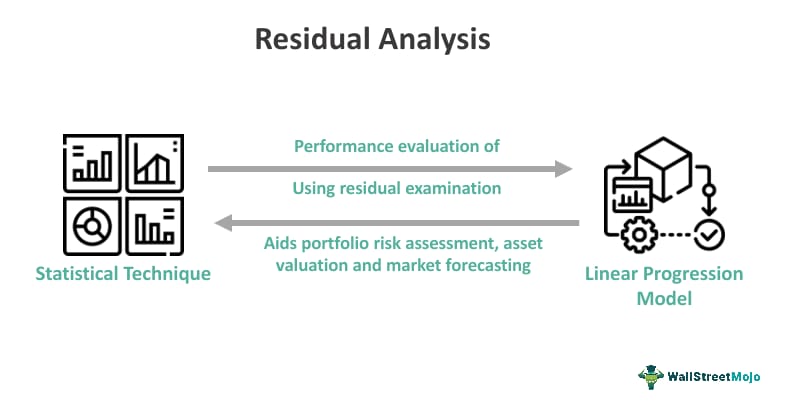

In performance evaluation and predictive modeling, the residual—the difference between observed and predicted values—serves as a critical diagnostic tool. When residuals consistently register as negative numbers, a compelling question emerges: does this signal an underestimation, or reflect limitations inherent in the model? Understanding the nuance behind a negative residual is essential for analysts, forecasters, and decision-makers who rely on data-driven accuracy.

Far from a simple sign of shortfall, residual negativity often reveals deeper dynamics about model assumptions, data quality, and the complexity of real-world systems.

The Role of Residuals in Predictive Accuracy

In statistical forecasting, residuals are the heartbeat of model validation. Defined as the discrepancy between actual outcomes and model-generated predictions, they provide insight into how well a model captures underlying patterns. A positive residual indicates the model overestimates, while a negative residual suggests it underestimates outcomes relative to reality.

Yet measuring the significance of a negative residual demands careful context—its interpretation depends on factors like data variability, measurement error, and the nature of the forecasting task.

Residual analysis forms the foundation of robust model validation. Analysts use residual plots, standard error calculations, and statistical tests such as the Durbin-Watson test to assess whether patterns exist that signal systematic bias. When residuals cluster around zero, forecasts are deemed unbiased; persistent deviations, whether positive or negative, indicate consistent performance gaps.

The sign alone—positive or negative—does not definitively diagnose underperformance—only invites deeper inquiry.

<>When residuals are consistently negative, does this confirm an underestimate, or reflects data limitations? This is the central question.The assumption that a negative residual automatically implies underestimation is a common but potentially misleading leap. Residuals capture a single dimension of model error—difference magnitudes—not whether the model systematically misses the mark.

A persistent negative residual could reflect genuine underprediction, especially in volatile or trending data. However, it might equally stem from training data constraints, selection bias, measurement noise, or omitted variables that degrade predictive capacity. In time-series forecasting, for example, models trained on limited historical windows may consistently lag behind emerging trends, generating negative residuals not out of error, but due to outdated patterns.

Consider a retail sales forecast powered by a regression model trained on past data from stable market conditions.

As economic shifts alter consumer behavior, residual residuals become negative—not because the model fails, but because the historical data no longer fully represent current realities. Similarly, in forecasting energy demand, a model built on seasonal averages may underestimate peak usage during unprecedented weather events, again resulting in negative residuals.

<>Several factors transform a negative residual from a warning sign into a symptom of deeper model limitations rather than a simple underestimation.First, data quality and representativeness profoundly influence residual behavior. If training data lacks diversity—underrepresenting certain events or trends—predictions inherently drift, generating systematic bias.

Residuals become negative not from error, but from model myopia. Second, model specification plays a pivotal role. Overly simplistic models, such as linear regressions applied to highly non-linear systems, struggle to capture complex relationships, consistently underestimating variability and producing negative residuals in volatile domains.

Third, measurement error distorts ground truth. When observed outcomes are inaccurately recorded—via sensor inaccuracies, human reporting bias, or lagging data collection—the model adjusts to flawed reality, often underestimating true values. Fourth, temporal misalignment commonly occurs.

Models trained on lagged data may fail to react swiftly to accelerating trends, leading to delayed and negative residual signals. Finally, seasonal or cyclical blind spots can cause persistent underestimation during peak periods when historical patterns no longer apply.

<>Residual negativity is not inherently an underestimate; context and root causes define its meaning.What, then, makes a negative residual a reliable signal of underestimation? It often emerges when both residuals and error metrics—such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE) or Root Mean Square Error (RMSE)—increase concurrently, suggesting not mere noise but systematic bias.

Analysts examine residual plots for trends or patterns, where consistent negative residuals correlate with specific conditions (e.g., high demand, economic booms), pointing to model lag rather than error. Cross-validation reveals whether the pattern persists across data splits, and sensitivity analyses test how alternative model structures affect residual behavior. Additionally, comparing forecasts against alternative models helps isolate whether negative residuals reflect true underestimation or are artifacts of poor model choice.

In practice, consider a city’s public transit ridership model.

If projections consistently fall short during holiday weekends—recorded via ticketing data showing 20–30% higher usage—counter-analyzing real-time sensor and historical anomaly data reveals model bias toward average weekday patterns. This negative residual, confirmed by rising error metrics and pattern persistence, signals genuine underestimation rather than random error. In contrast, a single spike in residuals due to a system outage—reflecting temporary disruption—would not justify broad underestimation conclusions.

Experienced analysts stress the importance of triangulation: no single residual value dictates truth.

A comprehensive evaluation incorporates residual analysis alongside qualitative insight, domain expertise, and stress testing across scenarios. Models must evolve—retrained on fresh data, updated to capture emerging trends, and adjusted to mitigate biases—to close the gap between predicted and observed outcomes.

A negative residual, therefore, is as much about diagnosing context as exposing error. It is not a static verdict but a signal demanding interpretation.

Underestimation may lie at its core, but only through rigorous, multi-dimensional analysis can analysts determine whether shortfalls reflect model frailty or reality’s complexity. This nuanced understanding transforms residual patterns from mystery into material insight, ensuring forecasts grow not just accurate, but actionable.

The next time a negative residual appears, resist the urge to label it an underestimate. Instead, ask: what does this pattern reveal?

What limits shape the model’s vision? With thoughtful scrutiny, residuals become not warnings of failure, but bridges to deeper understanding—grounding forecasts in truth, not just numbers.

Related Post

Channing Tatum’s Weight Gain Journey: From Hollywood Lean to Transformational Body Mastery

Heartbreaking Loss on Storage Wars: “Yup Guy” Dies Suddenly of Heart Attack

Top Hindi Movies to Watch on YouTube: A Must-See List Sweeping Streaming Platforms

JJTView Unlocks Spinal Journey: How J-JTBV Transforms Modern Diagnosis and Development