How Inertia of Rod Shapes Dynamics: The Unseen Force Governing Motion

How Inertia of Rod Shapes Dynamics: The Unseen Force Governing Motion

The inertia of a rod is not merely a theoretical concept confined to physics classrooms—it is a fundamental principle dictating how rigid structural elements resist changes in motion. Unlike fluids or flexible beams, a rod’s excellent structural integrity and high moment of inertia render it a cornerstone in engineering, architecture, and mechanical design. Understanding the inertia of rod reveals why certain shapes endure stress differently, enabling engineers to optimize designs for safety, durability, and performance.

From skyscraper columns to rotating machinery shafts, the rod’s resistance—known as inertia—plays a decisive role in stability and motion control.

The physical basis of inertia in linear elements lies in mass distribution and geometric properties. Specifically, a rod’s moment of inertia—a measure of resistance to angular acceleration—depends on both material density and spatial configuration.

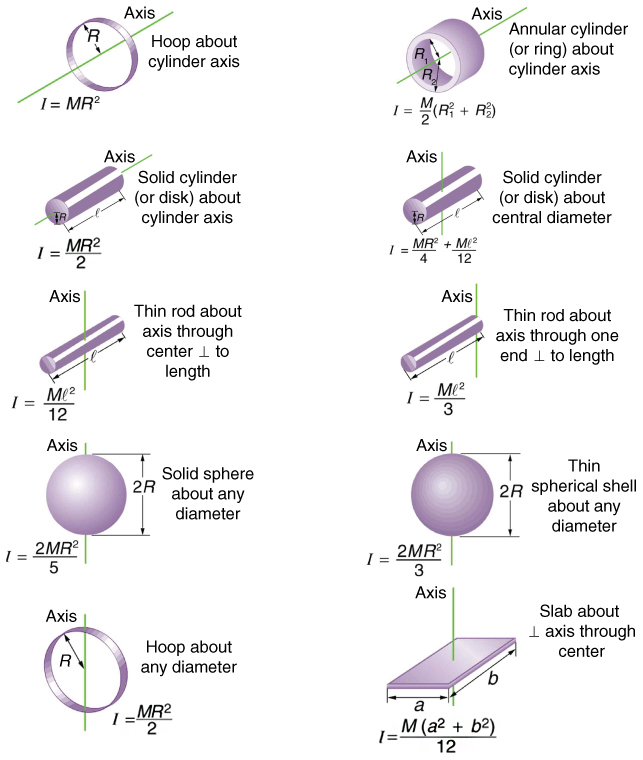

For a straight straight rod rotating about its center, calculated as I = (1/12)ML², the inertia quadruples with increasing length and mass squared, demonstrating how geometry directly amplifies resistance to rotational motion. “A longer, heavier rod doesn’t just weigh more—it resists changes in spin with enhanced strength,” explains Dr. Elena Torres, mechanical systems researcher at MIT.

“This is why structural rods in bridges and studios are calculated not just for load-bearing, but for inertial stability.”

The inertia of rod also explains critical behaviors under dynamic loads. Consider a rapidly accelerating crane arm: the rod’s inertia resists immediate angular change, requiring increased torque to initiate or stop rotation. Similarly, in precision robotics, a lightweight rod might vibrate unintentionally due to low inertia, whereas a denser, heavier rod suppresses oscillations—enhancing accuracy.

These real-world dynamics underscore the vital balance between mass, length, and rotational inertia in practical engineering.

Core Physics of Rotational Inertia in Rods: From Theory to Real-World Implications

The moment of inertia for a uniform rod quantifies this rotational resistance mathematically. While a point mass rotates about a fixed axis with simple momentum p = mv, a distributed mass like a rod demands integration over its extended structure.For a rod of uniform density and length L, the moment of inertia about its central perpendicular axis is I = (1/12)ML², a formula derived from calculus but intuitive in impact: doubling the rod’s length multiplies inertia by four, while doubling mass quadruples resistance.

This principle governs design choices across industries. In automotive engineering, heavy cylindrical rods are used in suspension components not only for strength but to dampen high-frequency vibrations caused by road irregularities.

The greater inertia dampens sudden motions, improving ride comfort and control. Likewise, in aerospace, carbon-fiber rods used in satellite booms leverage low density yet high moment of inertia to resist turbulent forces in orbit without excessive weight. “You’re trading mass for motion control,” notes Dr.

Marcus Wu, a senior consultant in structural dynamics. “A rod’s inertia isn’t a drag—it’s a tool for stability.”

In rotational machinery—such as gear boxes or flywheels—rods with optimized moment of inertia stabilize speed fluctuations. A heavy flywheel rod absorbs rotational energy surges, preventing abrupt speed drops under load.

This inertia-shaped damping boosts operational reliability, reducing wear and extending component life. In robotics, where precision drives performance, minimizing unwanted inertia helps eliminate overshoot and resonance, enabling faster, smoother operation.

Designing for Stability: Strategic Use of Rod Inertia in Engineering Applications

Engineers deliberately exploit the inertia of rod to enhance system performance.Structural columns in high-rise buildings, for example, are designed with high moment of inertia to resist lateral forces from wind or seismic activity. A solid steel column’s greater I-value compared to hollow or segmented alternatives provides superior rotational stability, preventing buckling and collapse. In seismic zones, moment-resisting frames rely on stiff, inertial rods to dissipate energy efficiently during ground motion.

In mechanical linkages and rotating assemblies, material selection and geometry fine-tune inertia for specific functions. A rotating shaft made of a dense alloy rod resists torsional vibrations better than one carved from lightweight composite, reducing fatigue and noise

Related Post

Liza Minnelli Health: A Legacy of Resilience and Innovation in Wellness

Exploring The Cast Of Rocky 5: The Final Chapter That Rewrote the Legacy of an Icon

Marty Byrde Unlocks Media’s Future: The Insider’s Blueprint for Success

How to Connect with ITV West Country: Get In Touch with Confidence