Does the President Stay President During Martial Law? The Constitutional Constraints and Real-World Tests

Does the President Stay President During Martial Law? The Constitutional Constraints and Real-World Tests

When authority is suspended and martial law declared, a fundamental question emerges: Can the sitting president remain in office, or must the executive be removed from power? This tension between continuity and accountability defines one of the most consequential legal and political dilemmas in democratic governance. Far from a theoretical debate, historical episodes reveal that presidents do not automatically retain office during martial law; rather, their status is governed by constitutional frameworks, statutory limits, and institutional checks—principles that shape how power is wielded, contested, and preserved in times of national crisis.

Martial law, by definition, suspends normal civil liberties and transfers executive powers to military or emergency authorities, placing governance under armed force. Yet, despite this radical shift, the U.S. Constitution and federal law explicitly condition the president’s authority.

The core principle is clear: no president—regardless of crisis severity—automatically remains president once martial law is declared. As legal scholar Harold Chung notes, “Martial law does not reset the presidency; it redistributes power, often abrogating presidential control over law enforcement and civil order.” This structural reality underscores a vital safeguard: the presidency survives, but not sans constraint.

Historical precedents illustrate this dynamic.

During the 1861 Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln maintained his office under suspended constitutional protections, justified by the exigencies of war and the need for executive action to suppress rebellion. But Lincoln’s authority existed within a context where Congress retained ultimate constitutional oversight—both branches operated in a system of balanced power. By contrast, more recent episodes, such as the 1970s imposition of national martial law in Washington, D.C., under President Richard Nixon, encountered sharp legal resistance.

Although Nixon declared a state of emergency, the act was narrowly defined, targeting specific civil disturbances rather than broad executive dominance. Crucially, the courts intervened, affirming that martial law powers are not absolute and must align with federal statutes and constitutional rights.

Constitutional mechanisms limit presidential continuity during martial rule in several key ways.

The U.S. Constitution vests executive power in the president but subject to congressional oversight and judicial review—principles that survive declared emergency states. Article II grants broad war and national security powers, yet these do not override the system of checks and balances.

The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 further restricts military involvement in civilian law enforcement, reinforcing civilian control. Additionally, many states have their own emergency statutes that define when and how martial authority can be declared—and by whom. Presidents cannot unilaterally extend emergency rule indefinitely; legislative or judicial action remains a necessary check.

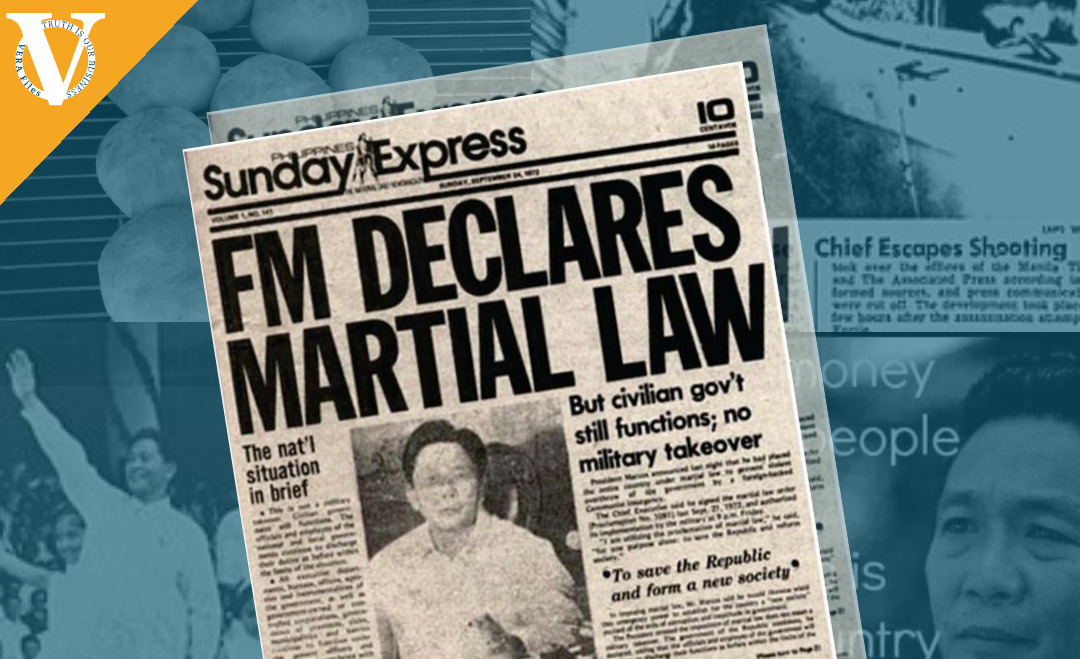

Historical examples highlight both adherence to and erosion of these norms. In 1987, during martial law declared by Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines (with diplomatic recognition from the U.S. at the time), President Marcos retained a facade of presidency, but martial authority bypassed constitutional mechanisms entirely.

His rule became authoritarian, with the judiciary dismantled and Congress suspended—demonstrating how martial law, when divorced from constitutional limits, enables catastrophic abuse. Conversely, during U.S. state-level emergencies, such as Detroit in 1980 or more recently in rural curfews, governors exercise emergency powers without fully dissolving constitutional order—preserving democratic sequencing even amid crisis.

Legal and practical realities emphasize that the president’s continuity during martial law is not guaranteed by holding office, but by compliance with constitutional boundaries. While some leaders attempt to preserve power through emergency decrees, institutional frameworks—Congress, courts, state legislatures—act as indispensable buffers. Judicial oversight plays a pivotal role: courts routinely reject executive overreach, affirming that “martial law suspends rights, but not executive immunity.” Courts have repeatedly held that emergency powers are conditional and revocable, never permanent or unchallengeable.

In sum, does the president stay in office during martial law? The answer, grounded in law and history, is that power endures—but only as long as it respects constitutional and statutory limits. Presidents remain president, not absolute rulers, in times of national emergency.

The framework resists concentration of authority, ensuring that martial rule serves defense, not domination. This balance preserves democratic integrity, proving that continuity and accountability are not opposites, but essential companions in sovereignty under stress.

Related Post

Is Brian Quinn In A Relationship? Unpacking the Personal Life of the Stand-Up Star

Transform Your Future: Top Nail Tech Schools in Virginia Advancing Careers with IIOnline & More

Mariemelons: A Journey Through Music and Culture That Transcends Borders

Unveiling the Mysteries Surrounding Michael Kitchen's First Wife