Do Prokaryotic Cells Have Vacuoles?

Do Prokaryotic Cells Have Vacuoles?

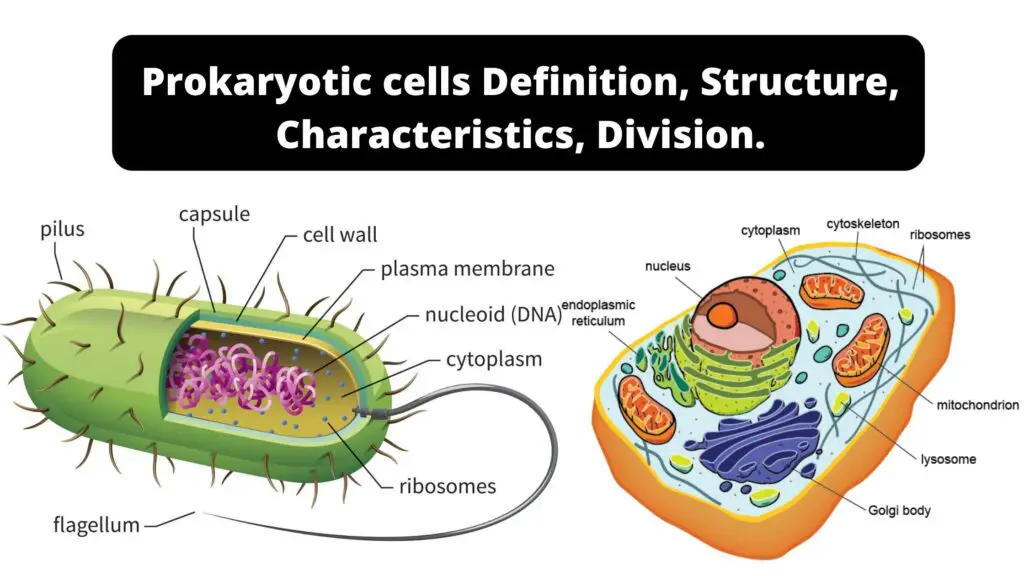

Beneath the microscopic surface of life, prokaryotic cells—among the oldest and simplest forms of life—reveal a cellular architecture that defies conventional eukaryotic norms. While vacuoles are hallmark features of complex eukaryotic cells, their presence in prokaryotes remains a subject of scientific precision and debate. Emerging research confirms that prokaryotes do not possess classical vacuoles as defined in eukaryotes, but they do exhibit similarly functional membrane-bound compartments with distinct evolutionary and biochemical significance.Unlike the expansive, water-filled vacuoles that store nutrients, segregate metabolic processes, and maintain turgor pressure in plants and fungi, prokaryotic cells rely on a more streamlined system.

These single-celled organisms—bacteria and archaea—lack membrane-bound organelles entirely, including vacuoles. Instead, their internal environment is organized through dynamic, fluid membranes that enable rapid responsiveness to environmental shifts. “Prokaryotes thrive not through compartmentalized vacuoles, but via membrane-associated functional zones—such as mesosomes and proton gradients that mimic vacuolar roles,” explains biophysicist Dr.

Elena Marlowe. “They achieve efficiency without enclosure.”

Structure Without Enclosure: The Prokaryotic Approach

Far from vacuoles, prokaryotic cells utilize specialized membrane invaginations and protein-rich microdomains to fulfill critical housekeeping functions. For instance:

- Carboxysomes: These protein-enclosed microcompartments concentrate enzymes for carbon fixation in cyanobacteria, enhancing metabolic efficiency—an evolutionary precursor to organelle targeting in eukaryotes.

- Memory Storage Membranes: Some bacteria maintain invaginated regions that store ions and metabolites, managed by selective transport proteins rather than lipid-bound vacuoles.

- Inclusion Bodies: While not true vacuoles, lipid droplet-like inclusions store polyhydroxyalkanoates or glycogen, regulated by environmental cues and metabolic demand.

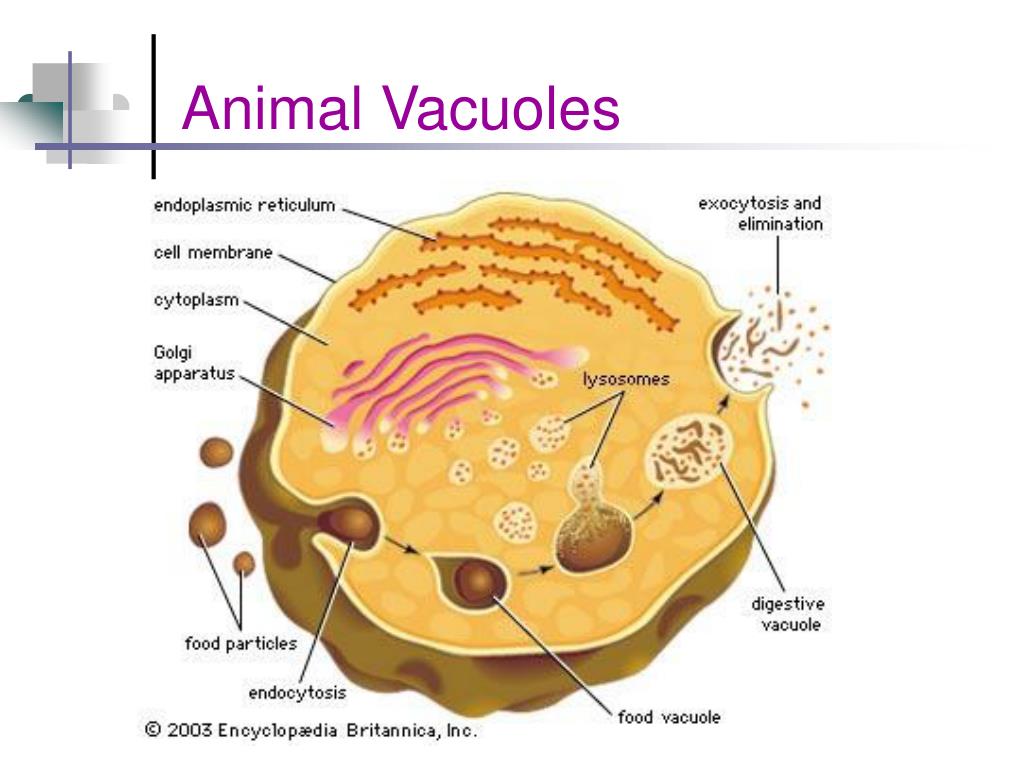

These adaptations contrast sharply with eukaryotic vacuoles, which are large, permanent organelles enclosed by a double membrane and essential for storage, waste processing, and signal integration.

“Prokaryotes compensate through rapid membrane remodeling\u2014fusing and splitting vesicles dynamically,” notes Dr. Samuel Gross, microbiologist at the Max Planck Institute. “This plasticity allows swift adaptation to stressors like nutrient scarcity or osmotic shock—without relying on static vacuolar structures.”

Functional Parallels, Not Identity

While prokaryotic cells lack true vacuoles, their internal organization reveals remarkable functional parallels.

Eukaryotic vacuoles serve as central hubs for transport and signaling; similarly, prokaryotic membranes coordinate ion gradients, nutrient uptake, and enzymatic compartmentalization through trafficked protein complexes and lipid domains. “Function drives form, but not in the way we associate vacuoles with eukaryotes,” says Dr. Marlowe.

“The same biological imperatives—efficiency, resource management, and survival—guided these divergent solutions.”

Consider this: vacuum-sealed, lumen-filled compartments in complex cells evolved much later, likely to support cellular complexity and niche specialization. Prokaryotes, constrained by size and simplicity, achieved metabolic sophistication through structural fluidity and strategic membrane control

Related Post

Mapping the Abyss: Helldivers Map Reveals the H Valentine’s Deepest Frontier

Özge Yağız Husband: A Deep Dive Into Their Romantic Partnership Beyond the Spotlight

DeanStarkTrapTsoh: Revolutionary Pest Control Mechanism Redefining Modern Trapping Efficiency

The Unstoppable Rise of Nhk Game: Japan’s New Gaming Powerhouse Redefining Interactive Entertainment