Between Groups vs Within Groups: Unlocking the Secrets of Group Behavior in Research Design

Between Groups vs Within Groups: Unlocking the Secrets of Group Behavior in Research Design

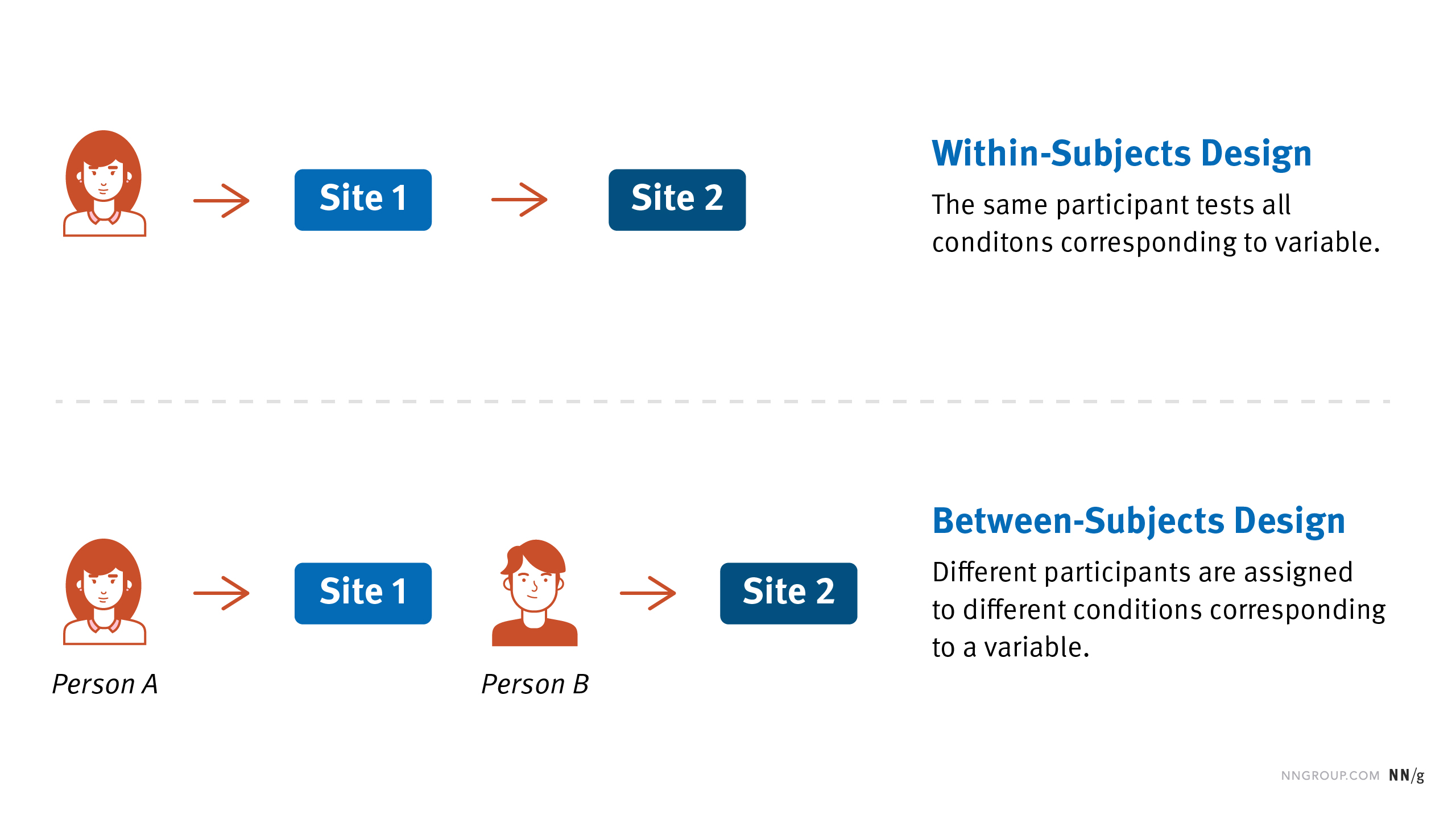

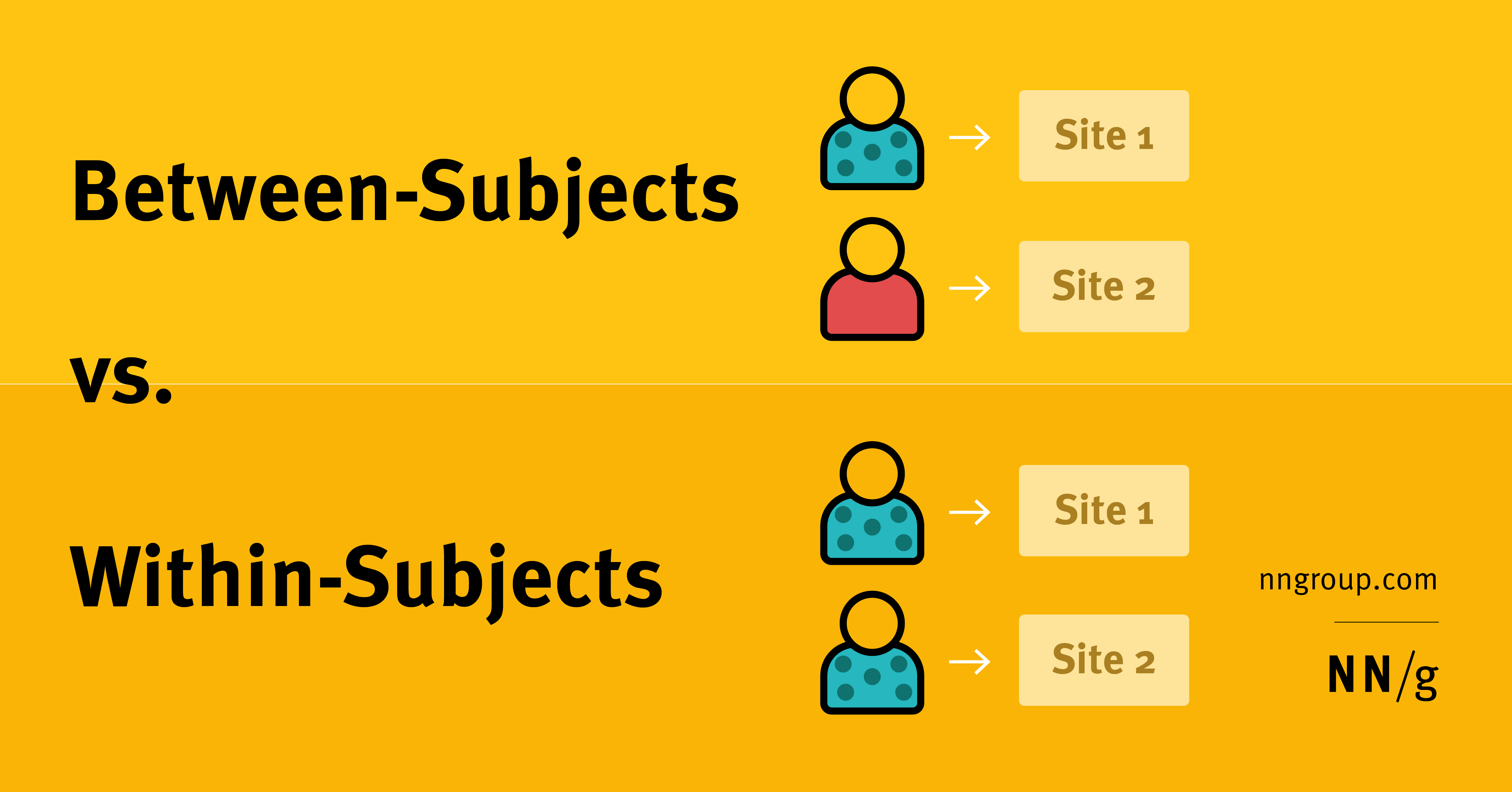

In scientific inquiry, understanding how individuals behave in different contexts hinges on a critical distinction: between-group effects and within-group effects. While both approaches reveal valuable insights, their design logic, sensitivity to change, and interpretive power differ fundamentally. Between-group comparisons isolate differences across separate populations—treating participants as static observers of distinct categories—while within-group methods examine dynamic shifts in the same individuals across conditions, offering a window into the malleability of human behavior.

This distinction lies at the heart of experimental validity, influencing everything from psychological research to organizational studies. Understanding Between Groups Design Between-group design, as the term implies, compares outcomes across two or more distinct populations. Each participant is measured once, fixed in a specific condition—such as treatment versus control—allowing researchers to identify permanent or stable differences attributable to group membership.

This approach excels when studying stable characteristics or fixed treatments: for example, comparing cognitive performance between individuals with diabetes and healthy controls. Because participants remain unchanged over time, any observed differences reflect inherent group traits rather than transient states. Because participants remain unchanged over time, any differences reflect inherent group traits rather than temporary conditions.

Conservatively, between-group comparisons reduce confounding by holding participants constant, strengthening causal inference when randomization is properly applied. However, such designs struggle to capture change over time or responses to interventions that unfold gradually, limiting insight into developmental or experiential processes.

The Power and Limits of Between Groups in Experimental Setups

One of the primary strengths of between-group methodology lies in its simplicity and robustness.By holding participants fixed across conditions, researchers minimize variability unrelated to the experimental variable—known as error variance—thereby increasing statistical power. This is particularly crucial in controlled lab settings where intervention effects must be isolated with precision. For instance, in a clinical trial testing a new antidepressant, participants receive treatment or placebo and are assessed only post-intervention.

The primary task becomes determining whether group membership alone causes differences in symptom severity. Yet this design comes with limitations. Since participants are measured only once, it cannot capture trends, growth, or behavioral shifts over time.

In educational research, comparing test scores between students who studied with flashcards versus those who used digital tools offers a snapshot, but not insight into how learning unfolds across weeks or months. Moreover, between-group studies may miss within-individual variation—important in psychology, where personality, motivation, and performance fluctuate dynamically. “A person’s behavior isn’t always consistent across contexts,” notes Dr.

Elena Martinez, a behavioral scientist at Stanford University. “A writer might produce thoughtful work in isolation but struggle under deadline pressure. Between-group designs risk oversimplifying such complexity.”

Between-group comparisons remain indispensable for establishing group-level causal relationships, particularly when temporal order and treatment specificity are paramount.

They form the backbone of randomized controlled trials and cross-sectional studies, where clarity of group distinctions drives policy and practice. But when change—rather than comparison—is central, this approach falls short.

Navigating Within Groups: Tracking Change Over Time

In contrast, within-group design dynamically observes the same individuals across multiple conditions, time points, or interventions. By repeatedly measuring the same subjects—such as tracking anxiety levels before, during, and after a mindfulness program—researchers uncover patterns of adaptation, response, and growth that between-group designs cannot detect.This temporal focus reveals how individuals react to change, no longer defined solely by static group labels. Within-group methods thrive in longitudinal, pre-post, or repeated-measures contexts. Clinical trials often employ this strategy: patients undergo screening, receive treatment, and are reassessed weeks later.

The focus shifts from “What group differs?” to “How does the same person change?” This approach is particularly powerful in psychology and education, where individual development shapes outcomes. For example, studies measuring academic resilience might assess students’ stress responses over a school semester, showing not just average differences, but variation in personal trajectories and recovery patterns after setbacks.

Statistical models tailored for within-group designs—such as repeated measures ANOVA, mixed-effects regression, and growth curve modeling—allow nuanced interpretation of intra-individual change.

These tools disentangle consistent trends from random noise, offering richer insight than simple before-and-after comparisons. “Without tracking change within individuals, we risk overlooking delicate but meaningful shifts,” explains behavioral statistician Dr. Rajiv Nair.

“A student might score average relative to peers, but within-group analysis could show a sustained upward trend—indicating profound personal growth that between-group design alone would miss.”

Yet within-group designs face unique challenges. Participants’ familiarity with testing conditions or fatigue from repeated assessments introduces potential confounding. Say, a wellness intervention requiring daily journaling may yield diminishing returns as monitoring becomes routine.

Moreover, statistical control for individual differences demands sophisticated modeling, and missing data can skew results if not properly addressed through techniques like mixed models.

While within-group designs expose dynamic human experience, they require careful planning to sustain engagement and minimize bias over time. Neither alone captures the full complexity of

Related Post

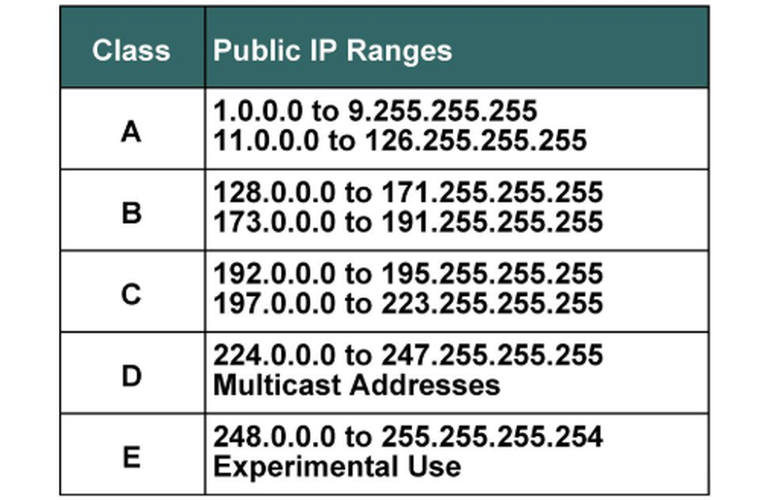

Unlock Your Digital Identity: Discover Your Public IP Address with IP Chicken’s Free Lookup

Porsha Williams, Celebrities Embrace Natural Beauty During Self-Isolation with Unfiltered Makeup-Free Selfies

Setf: The Engine Driving Secure Software Systems in a Vulnerable Digital Era

Discover Omaha Zoo like Never Before: Your Complete Mapping Guide Through the Wildlife Capital