Absolute Advantage vs. Comparative Advantage: The Secret Engine of Global Trade

Absolute Advantage vs. Comparative Advantage: The Secret Engine of Global Trade

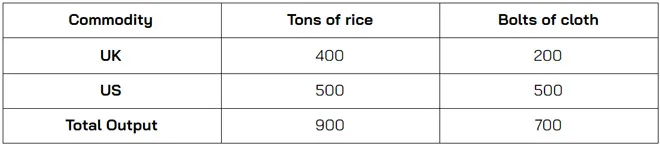

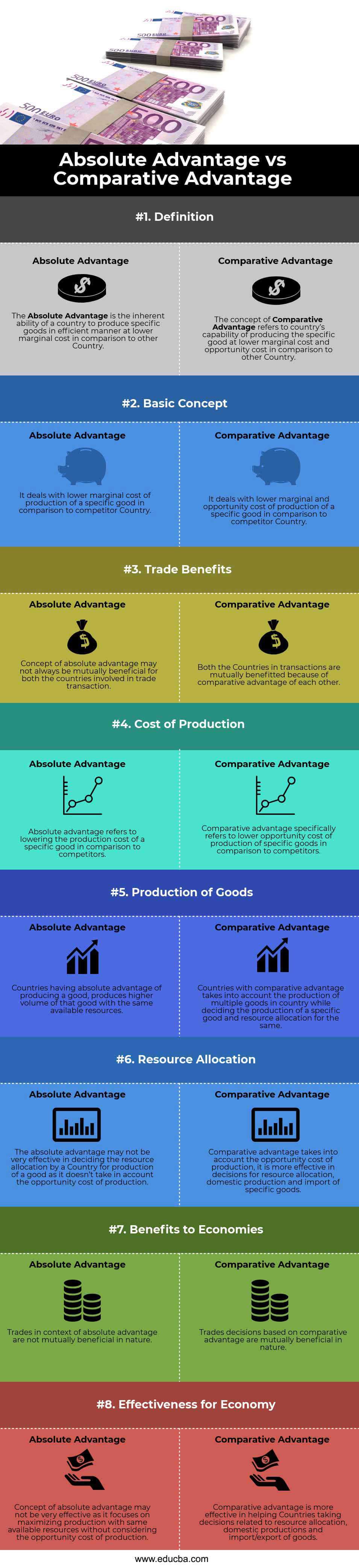

In the intricate machinery of international commerce, two foundational concepts—absolute advantage and comparative advantage—serve as guiding principles for understanding how nations optimize productivity and wealth creation. While often conflated, these economic theories reveal distinct mechanisms behind trade efficiency: one rooted in raw production capacity, the other in relative opportunity costs. Absolute advantage identifies which country can produce more of a good with the same inputs, whereas comparative advantage exposes the hidden value in specializing based on relative efficiency, even when a nation is less efficient overall.

As global supply chains grow more intertwined, grasping these differences clarifies why trade—despite apparent paradox—fuels prosperity for all participants.

The Paradox of Absolute Advantage: When Strength isn’t Always Enough

Absolute advantage, first articulated by Adam Smith in 1776, asserts that a country enjoys absolute advantage in producing a good if it can output more of it using identical resources than any other nation. This straightforward metric paints a clear picture: a nation with superior technology, abundant natural resources, or massive scale may dominate absolute production in certain industries.Consider Saudi Arabia’s dominance in oil extraction, where vast reserves and low extraction costs enable it to produce barrels at a fraction of the global average. Similarly, the United States leads in farming key commodities like corn and soybeans, leveraging mechanization and fertile land to generate vastly higher yields per hectare than many developing nations. These absolute strengths form the foundation for trade leverage.

A nation with absolute advantage can flood global markets, undercutting inefficiencies and driving down prices—benefiting importing countries by lowering consumer costs and raising global output. Yet absolute advantage alone tells only half the story. A country may produce everything more efficiently—yet still lose trade benefits without strategic specialization.

Because every nation faces different opportunity costs—resources allocated to one sector mean they cannot be used elsewhere—the full value of trade emerges only when countries focus on what they sacrifice least to produce.

The Hidden Power of Comparative Advantage: Specialization Through Opportunity Cost

“Comparative advantage isn’t about being the best—it’s about being relatively better,” says economist Paul Krugman. This insight, refined by David Ricardo in the early 19th century, reveals that trade gains stem not from absolute production superiority, but from relative efficiency and opportunity cost.Comparative advantage hinges on the cost of forgoing alternative uses of resources. A nation holds a comparative advantage in producing a good if it incurs a lower opportunity cost compared to others. To illustrate, suppose Country A can produce both wheat and cloth, but with opportunity costs of 2 bushels of wheat to make one cloth, and 5 bushels in Country B.

Even if Country A produces both faster—absolute advantage in both—the laws of comparative advantage dictate that Country B should specialize in cloth, where its lower opportunity cost makes the trade mutually beneficial. Country A, then, focuses on wheat, even if less efficiently. This dynamic drives global efficiency: resources flow to higher-value uses, lifting total output.

For example, countries with rich labor forces specialize in labor-intensive manufacturing, while resource-rich nations focus on raw material extraction. The result? Lower prices, greater variety, and expanded economic frontiers—trade’s true invisible engine.

Real-World Applications: Agriculture, Industry, and the Global Supply Chain

In agriculture, comparative advantage shapes trade patterns worldwide. Brazil’s vast tropical lands support high-yield soy and coffee production, where low land costs and favorable climates reduce opportunity costs. Meanwhile, France’s advanced farming techniques and subsidies allow efficiency in wine and dairy, despite higher labor expenses.International buyers—and consumers—benefit from accessing these specialized outputs at competitive prices. Industrially, technological pace defines modern advantage. Germany’s leadership in precision engineering creates a true comparative edge in high-value machinery, even as other nations mass-produce lower-cost goods.

Similarly, China’s dominance in rare earth minerals—critical for electronics and green energy—stems not only from scale but from relatively low opportunity costs due to specialized infrastructure and workforce training. These examples underscore a key truth: absolute production dominance rarely equates to sustained trade superiority. A country’s true advantage lies not in doing everything best, but in allocating resources to areas where its relative efficiency creates the greatest gains.

The Economic Impact: Trade Flows and National Wealth

When nations apply comparative advantage through strategic specialization, global trade transforms inefficiencies into shared prosperity. Consider retrograde logic: if all nations focus solely on absolute output, wasteful duplication increases costs and limits access to needed goods. But when trade leverages comparative strength, GDP expands through optimized resource use.For importing countries, lower prices boost purchasing power and living standards. For exporters, targeted specialization expands markets and incentivizes innovation. Japan’s post-war shift to electronics and automotive specialization—backed by comparative strength in high-tech manufacturing—turned it into an economic powerhouse.

Conversely, Geneva’s dominance in horology and watchmaking rests on niche expertise and high-value branding, a modern echo of comparative advantage in microeconomics. Trade driven by comparative advantage also mitigates geopolitical friction. Nations depend on each other, creating mutual incentive for cooperation.

Disruptions—natural disasters, tariffs, or geopolitical tensions—highlight fragility, yet underlying economic logic remains resilient.

Challenges and Misconceptions in Applying the Principles

Despite theoretical clarity, real-world application faces practical hurdles. Political barriers, subsidies, and protectionism often distort comparative advantage, skewing trade flows.Developing nations may lack infrastructure or education to build specialized strengths, limiting their ability to compete. Moreover, short-term job displacement in non-competitive sectors can spark public resistance, complicating long-term reforms. Yet economists emphasize that these friction points do not invalidate the model—they underscore the need for complementary policies.

Investment in education, innovation, and infrastructure strengthens a nation’s relative edge. Trade agreements that reduce barriers and intellectual property protections enable smoother specialization. Only through such support does comparative advantage evolve from theory into tangible gain.

The Future of Trade: Aligning Absolute and Comparative Strength

Looking ahead, digitalization and green transitions redefine comparative advantage. Renewable energy leaders—Chile in solar, Iceland in geothermal—leverage unique natural assets to gain comparative edge. Meanwhile, automation shifts labor-intensive advantages, pushing nations to specialize in oversight, design, or verified quality.Absolute advantage evolves: economies with renewable resources gain not just dominance, but sustainability—a modern form of economic edge. Meanwhile, comparative advantage deepens through supply chain integration and cross-border industry clusters. Vietnam’s rapid rise in electronics assembly, powered by global components and local assembly expertise, exemplifies how relative positioning—combined with strategic upgrading—fuels growth.

In a world increasingly defined by interdependence, understanding the dance between absolute and comparative advantage remains essential. It reveals that true economic strength lies not in isolated efficiency, but in strategic focus—specialized, collaborative, and forward-looking. Countries that harness both principles will shape the future of global prosperity, turning diversity into shared gain.

Absolute advantage reveals raw productive capacity; comparative advantage uncovers the hidden power of opportunity cost. Together, they form the dual pillars of trade theory—guiding nations toward smarter specialization, higher output, and inclusive growth. As global markets continue to evolve, this economic duality will remain the compass for efficient, equitable, and enduring prosperity.

Related Post

How Many Sticks Is A Half Cup Of Butter? The Simple Conversion That Matters in Every Kitchen

Discovering The Life And Achievements Of Symone Blust: A Trailblazer in Innovation and Advocacy

ICICI India to UK Money Transfers: Navigating Fast, Safe, and Transparent Global Funds Flow

Get the Full Story on Lincoln City News — From Local Hallmarks to Community Voices