1850 Middle East Unveiled: How the OSCWorldSc Map Redefines Historical Understanding

1850 Middle East Unveiled: How the OSCWorldSc Map Redefines Historical Understanding

In 1850, the Middle East existed on the edge of transformation—amid shifting empires, ancient trade routes, and the quiet rise of modern cartographic ambition. The OSCWorldSc Map offers a rare window into this pivotal year, revealing a region far more interconnected and politically layered than long publications suggest. With meticulous detail, this digital reconstruction uncovers hidden patterns of power, commerce, and cultural exchange, reshaping how historians interpret the pre-modern landscape.

Far more than a static image, the map is a narrative document, capturing the dynamics of a world on the cusp of upheaval.

The OSCWorldSc Map of the Middle East in 1850 is not merely a relic of 19th-century mapmaking; it is a historically rich, data-laden visual timeline. Created through a fusion of archival sources, Ottoman surveys, European exploratory accounts, and regional tribal knowledge, the map integrates political boundaries, tribal territories, trade networks, and key urban centers with remarkable precision for its era. Unlike many contemporary maps, which often imposed arbitrary European geopolitical lenses, this map reflects indigenous spatial understandings and administrative realities close to what local powers and populations experienced.

The Cartographic Patchwork of a Fragmented Region

By 1850, the Middle East was a mosaic of overlapping sovereignties and spheres of influence.

The Ottoman Empire, though still dominant, faced mounting internal challenges and external pressures from expanding European interests. The map reveals sharp political boundaries—or absence thereof—in key areas like the Arabian Peninsula, the Fertile Crescent, and the Levant. Regional emirates, tribal confederations, and autonomous city-states maintained distinct identities, often determining their allegiances through pragmatic diplomacy rather than rigid allegiance to a central authority.

This decentralized structure is vividly portrayed through varying iconography and labeling choices that distinguish Ottoman-controlled zones, minority-run territories, and nomadic domains.

Key urban centers such as Cairo, Baghdad, Damascus, and Aleppo anchor the map, but their prominence is framed within broader socio-economic networks. Trade routes—caravan paths linking the Red Sea to Mesopotamia, and from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf—are rendered with precision, highlighting how commerce shaped settlement patterns and regional power.

The map underscores that economic vitality, not just territorial control, defined influence. “The real strength of the map lies in its ability to show not just borders, but flows—of goods, people, and ideas,” notes Dr. Layla Haddad, a historian specializing in Ottoman spatial administration.

Urbanization, Tribes, and the Web of Authority

Urban life in 1850 Middle East cities reflected both continuity and change: bustling markets dotted with caravanserais, mosques, and administrative centers, alongside emerging European-style consulates and foreign trading posts.

Yet beyond city walls, tribal networks wielded immense influence. The OSCWorldSc Map captures key tribal territories—often labeled with linguistic and familial markers—demonstrating how kinship and allegiance shaped political realities in remote and semi-peripheral regions. These tribal alliances often mediated conflict, determined tax collection, and influenced regional stability in ways invisible on more centralized state-focused maps.

Equally telling is the map’s depiction of religious and ethnic enclaves. Christian monasteries in the Levant, Shia shrines in Iraq, and Jewish communities in Aleppo are marked not just by labels but by spatial relationships that reflect coexistence, competition, and community autonomy. Such details contradict simplistic narratives of religious division, revealing instead a region of overlapping, sometimes fraught, but enduring pluralism.

“Each line and symbol tells a story of identity and interaction—how people lived, worked, and defended their place in a complex web,” explains Dr. Omar Farsi, a scholar of pre-modern Middle Eastern demography.

Infrastructure and Innovation Beneath the Surface

The map reveals nascent efforts at modernization that presaged 19th-century reforms.

Railroads, though still sparse, are emerging along critical corridors—especially in Egypt and along Ottoman military lines—signaling a shift toward faster communication and troop movement. Quarries and mineral outcrops are annotated with reference to resource extraction, pointing to strategic economic interests hidden beyond the imperial apexes. Roads, though rudimentary, connect urban nodes and trade hubs, underpinning a quiet transformation in regional connectivity.

Water sources—including wells, wells, and seasonal rivers—are prominently charted, reflecting the region’s enduring dependence on hydrology. Settlements cluster tight to these lifelines, emphasizing how geography dictated survival and expansion. The map thus serves as a foundational resource for understanding pre-colonial economic geography, with careful attention to environmental constraints and opportunities.

Mapping Identity: Language, Diplomacy, and Power

Language plays a critical role in the OSCWorldSc Map’s nuanced portrayal.

Place names appear in Arabic, Persian, Turkish, and local dialects, reflecting multilingual realities and competing claims to territory. Diplomatic markers—carved encampments, caravan agreements, and treaty blueprints—trace negotiations between local rulers, Ottoman administrators, and European envoys, revealing a competitive diplomacy that shaped borders long before modern statehood. These annotations transform a purely geographic tool into a historical diplomat’s ledger, underscoring that maps are never neutral—they are instruments of ambition, recognition, and control.

The Legacy and Limitations of the 1850 OSCMap

While the OSCWorldSc Map of the Middle East in 1850 provides unprecedented insight, it is not without historical constraints.

Indigenous oral histories and archaeological evidence occasionally diverge from cartographic representations, suggesting discrepancies in boundary claims or settlement patterns. Moreover, as a 19th-century synthesis, it reflects the era’s biases and limited access to interior regions—some tribal zones remain blurred or generalized.

Yet these limitations do not diminish the map’s value.

Instead, they invite critical engagement, prompting historians to cross-reference multiple sources for a fuller picture. The map’s enduring strength lies in its synthesis of diverse data into a coherent, visually compelling narrative—bridging past and present with factual integrity. It stands as both a record and a catalyst—a reminder that even historical maps carry urgency, capable of reshaping how we understand the roots of today’s complex geopolitical landscape.

In 1850, the Middle East was not a static map of empires but a living, breathing tapestry of people, power, and place. The OSCWorldSc Map transforms static history into dynamic discovery, proving that even old cartography, when reimagined, has the power to reveal truths once obscured by time.

Related Post

Breaking Barriers in Justice: How Greater Bakersfield Legal Assistance Inc. Empowers the Community

MotoGP Testing on TNT Sports: What Fans Can Expect—and Why It Demands Your Attention

Define Utopian Society: The Blueprint of an Ideal World

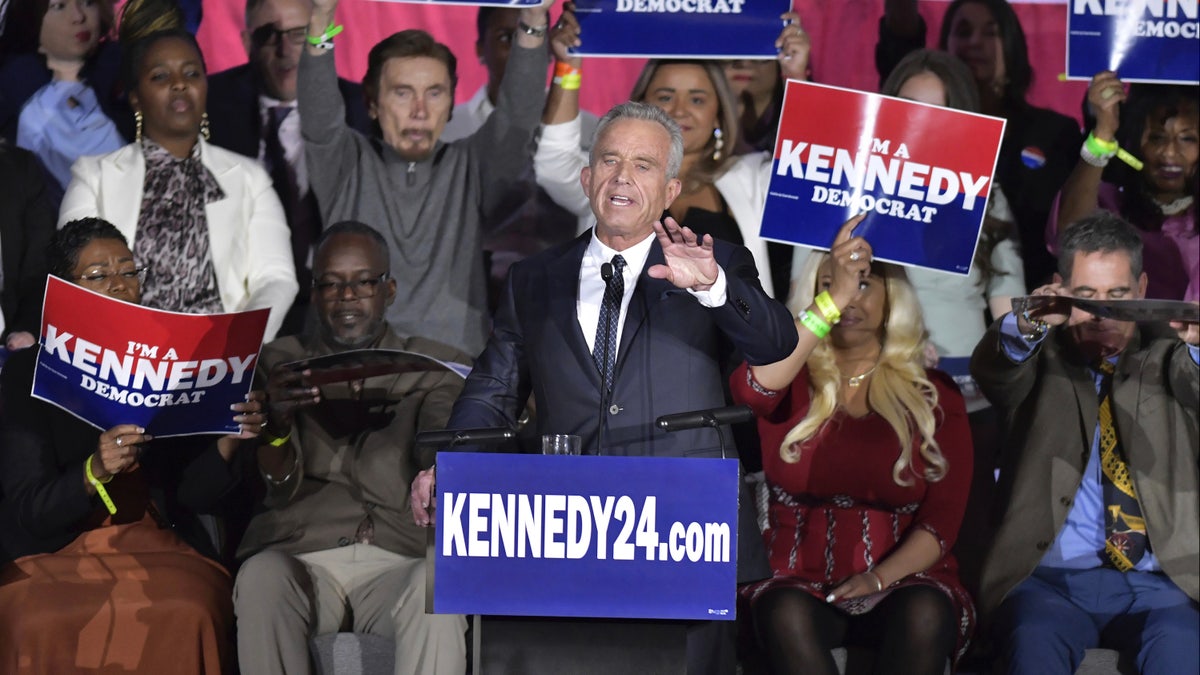

From Advocacy to Dynastic Legacy: Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s Children Carry a Family Name Built on Impact and Purpose